A Place of Awakening

To begin, could you briefly introduce yourself—who you are, where you’re based, and how you first encountered Aikido?

At a foundational level, I’m the father of five and grandfather of eight.

I live in Northern California on land that was part of the coastal Miwok territory. On this land, I restored an old working barn and turned it into a dojo—a place of training, or more deeply, a place of awakening.

It’s just 50 meters from my house, so I joke that I have a 50-meter commute.

I’ve been practicing Aikido since 1972, but my path began earlier—around age 12 or 13—when I started judo. My family moved often, and I was always the new kid, which brought taunts and sometimes physical confrontations.

My mother thought I was a bully, but mostly, I was just scared. After one too many torn shirts and bloody noses, she asked my principal what to do with me. He suggested judo. She was horrified, but I went to a class on a U.S. military base, where my father was stationed.

There, I saw about a dozen men in white uniforms throwing each other, then getting up smiling. It wasn’t about fighting—it was graceful, powerful, skillful action under pressure. I was hooked.

Every time we moved, I sought out a dojo—judo, jiu-jitsu, karate, whatever I could find. It became a kind of home for me. Then in 1972, living on the remote island of Kauai, I found an Aikido dojo. It felt like being a Catholic in the Vatican—I just knew: this is it.

I would drive across the island three nights a week to train. While others were watching sunsets or smoking joints, I was in the dojo. I was in love.

Continuing to Be a Beginner

How has five decades of Aikido shaped your being and your view of life?

One thing that stands out is the power of continuing to be a beginner.

Even though I’m what the Aikido headquarters in Japan would call a shihan, or master teacher, I’m still enthralled with it every day. I still have a living teacher. And I’ve learned that when I’m under pressure—whether real or perceived—I have a choice.

That ability to choose didn’t come overnight; it came through decades of practice and being under pressure again and again.

In Aikido, there’s always an attacker and someone who resolves the attack. It’s not a sport, and it’s not a combative art, but it is a powerful self-defense and a deep spiritual path. Over time, I began to see that these attacks in the dojo mirrored what I was encountering in daily life. People weren’t physically trying to strike me, but they might say things that triggered me in the same way. The practice helped me notice that—and respond rather than react.

Another thing Aikido has taught me is how to be fully here—in your own length, width, and depth—with a clear organizing principle, a purpose.

But it also teaches connection: it’s not just about you, and it’s not just about the other. It’s about holding both at once. That’s what “Ai-Ki” points to: being in harmony with life, with universal energy, with others.

The Body is the Doorway

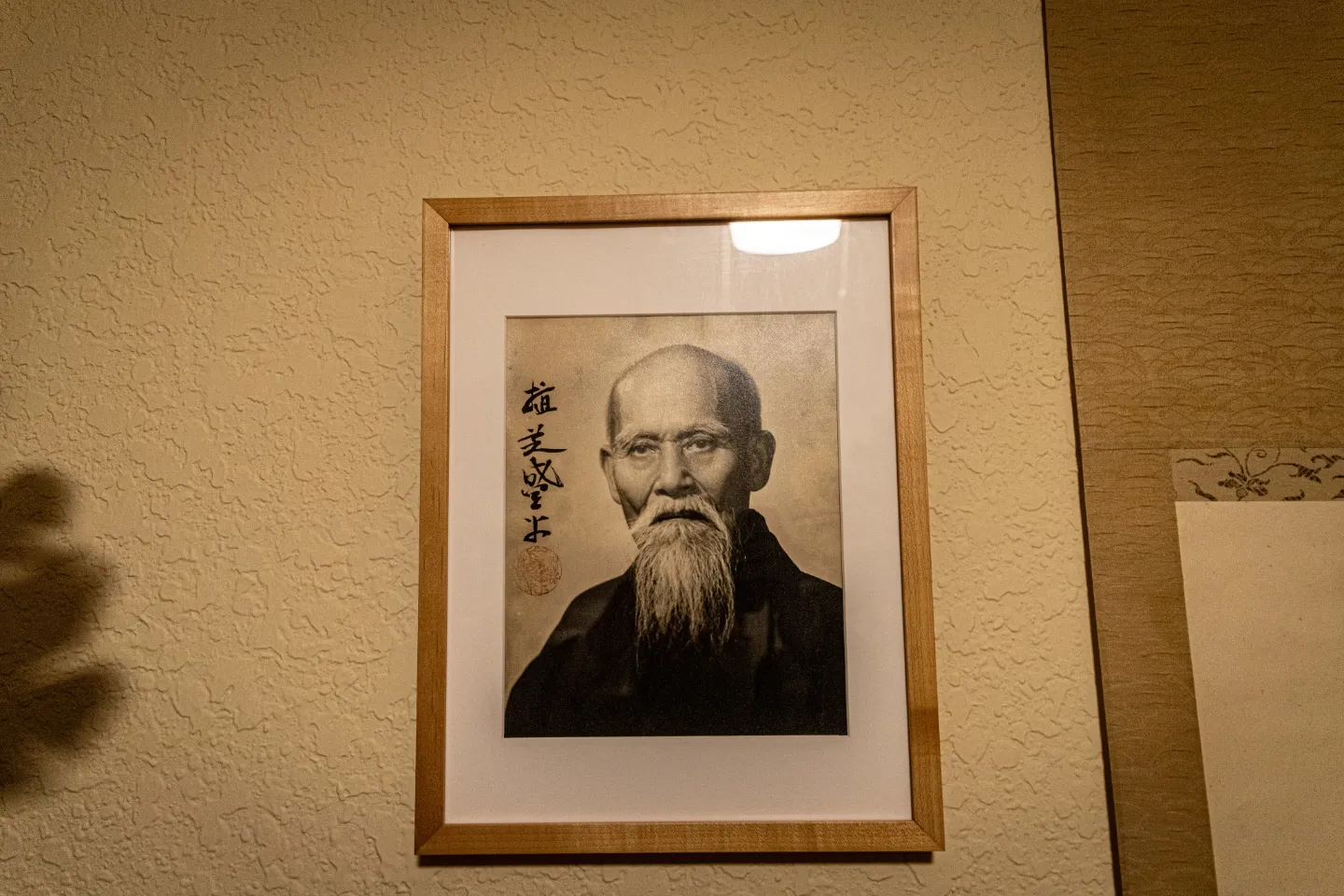

You have shared how seeing an image of Aikido’s founder, Morihei Ueshiba, had a magnetic effect on you. What about him and his presence instantly moved you?

Just before I moved to Kauai, someone showed me a book about Aikido. In it, there was a photo of Morihei Ueshiba—O Sensei—walking alone down a dirt path, surrounded by tall coniferous trees, holding a wooden sword.

There was something about how he carried himself, something transmitted through that photo—a powerful, living presence. I was in my mid-20s at the time, and I remember thinking: I want some of that. About six months later, I began practicing Aikido.

What I’ve come to understand is that even as a young man, O Sensei was always drawn to spiritual practice—particularly in the Shinto tradition. At the same time, he was deeply committed to the martial arts. He saw his father beaten once, and vowed never to let that happen again. He built himself up physically and became a national living treasure of Japan.

That union—of spiritual seeking and martial practice—is what drew me in. Aikido, for me, became a path into a deeper awakening, where the body is the doorway.

Returning to Center

You just mentioned returning—and from working with you before, I know centering is a key part of that. Could you speak about what centering is in Aikido and how it applies to life?

In Japanese, the word often used is hara—your belly center.

There’s a whole mythology and depth of meaning behind that word. But through my teachers, my own practice, and the students I’ve worked with, what I’ve come to embody is something we simply call “being centered.”

Being centered means you’re present. You’re present not only to other people, but to the environment—stones, grasses, trees, the four-leggeds, the crawlers, the winged ones. You’re open to what’s around you.

It also means you’re open to possibility. You’re not fixed or rigid in your worldview—you’re not saying, “This is the only way.” You’re available to new ways of seeing and responding.

And third, you’re connected to what you care about. In a sense, being in your hara—your center—is like being in your heart center. It’s where your purpose lives. So I often ask people: for the sake of what are you on this earth walk?

To be centered is to be aligned with that.

Is there a concept within Aikido that’s especially meaningful to you?

Yes—shugyō. It’s often translated as “austere training,” but I understand it as the cultivation of the self.

Yes, you’re learning to blend with an attack, to throw someone, to move out of the way—but at its heart, the training is about refining yourself. It’s rigorous, it’s heartfelt, and it demands energy and attention. It’s a discipline that’s both physical and spiritual.

This is beautifully reflected in what the famous Zen monk Dōgen said: “To study the path is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be one with all things.”

That’s the essence of shugyō—and also what grounds my work in meditation and somatics. It doesn’t mean I don’t make mistakes. But it gives me a way to return. I may go the wrong way—but I’ll get another chance.

Meeting Conflict with Presence

What are some of the qualities Aikido evokes in us that you feel are most needed in the world today—and that you hope to offer a glimpse of in your sessions?

One of the key things we learn is how to meet conflict or aggression without collapsing or becoming aggressive ourselves. Aikido teaches us how to neutralize violence—not by neutralizing the person, but by recognizing the human being behind the behavior.

Often, when someone comes at you with aggression, it’s a learned behavior. But underneath that, there’s a person trying to take care of what matters to them—just like you are. Their family, their safety, their livelihood. Aikido helps us see past the surface—the bluff, the haughtiness, the fear—and recognize that shared humanity.

There’s a principle in Aikido called musubi, which means to tie in, or to blend. In every practice, in every technique, our first move is to connect. Not to block, not to push away, not to dominate—but to blend with the energy of the other.

This is something we can carry into conversations and relationships. When someone disagrees with you, instead of reacting or shutting down, can you stay in your body in a way that signals: I’m here. I’m listening. I’m not trying to erase your perspective. I’m willing to hear you—and maybe even reflect back what I’ve heard, to make sure I understand.

When people feel that, something shifts. They no longer feel they have to defend themselves. They feel met. And even if you disagree, there’s a shared ground to stand on.

That’s where healing begins. That’s where we stop seeing people as “the other.”

There’s a line in the Upanishads: “Where there is the other, there is fear.” And it’s often out of fear that we overreact.

The Seen, the Unseen, and the Sacred

You’ve spoken about Aikido as a path through the body toward spirit—and that there are three stages to this. Could you share what those are?

There are three stages I often speak about.

The first is what’s manifest—what you can see. In Aikido, this is the physical technique: how someone moves, their posture, their timing. You can watch someone perform a technique and see if they’re embodying the principles or not.

The second is what’s hidden, or unseen. That’s the level of intent. Why is the person practicing? What’s motivating them? They might be learning a particular throw, but underneath that, there’s a purpose—maybe they want to build confidence, or learn to move through fear. In Japanese, this is sometimes called the secret or inner aspect. But if you become an acute observer of human beings—which Aikido can help with—you can often sense this intent in daily life too, even in how someone stands in line at the grocery store.

And then there’s the third stage, which I call the sacred—or the divine. This is the sense that there’s a larger energy, a life force, that moves through us. It’s beyond personality, beyond social roles or ego. It’s something we can touch through disciplined practice, and it allows us to move in the world with more respect, compassion, wisdom, and skill.

Returning to the Body

You’ve spoken before about how overidentified we are with the thinking self. Does Aikido offer a path back to embodiment—and how does that open up new ways of experiencing connection or even divinity?

That’s a very rich question.

I’ve met many people who are masters of their art—whether it’s Aikido, Capoeira, Kali, or another martial discipline. You’d absolutely say they’re “in their bodies.” Just like when you watch professional athletes: they’re precise, powerful, elegant.

But at the same time, you can be in your body in a way that’s purely performance-driven. The body becomes like a machine—trained to execute.

What Aikido offers is something different. It’s not just technical mastery. The movements in Aikido echo patterns we see in nature, in the solar system. Through those movements, we begin to tap into an energy that’s not ours alone. We start to recognize we’re part of something larger.

That changes how we live in our bodies—not just as performers, but as fully human beings. Human beings who are capable of shifting the narrative—especially the one that says we must fight to protect what’s ours.

Because when we’re fully in our bodies and present with others, we can see: there’s actually enough. There’s a way forward. We can figure it out together.