The Essence of the Way of Tea

Where did you grow up and how did this influence who you are now?

Due to my father’s work as a diplomat, I spent most of my childhood abroad. I was born in Seoul, and have lived in Moscow, Hawaii, Damascus, Kyiv, and Tokyo. For university, I decided to study in Kyoto where I currently live.

Since I have lived in multiple countries, I do not feel associated with a particular nationality or way of thinking. My childhood experience has helped me accept diverse perspectives.

The Japanese Way of Tea has its roots in ancient China, where tea was drunk among the Buddhist monks. It is said that Christianity, which was introduced to Japan by the Portuguese, influenced the Tea culture that flowered among the feudal lords.

Apart from Buddhism and Christianity there are elements of Daoism, Confucianism, and Shintoism. I feel that this practice of Tea is like a cup that can be filled with any flavor that humanity has to offer.

What for you is the essence of the way of tea?

I feel that the essence of tea is keeping or having the heart and the mind of a sun, and what I mean by that is the sun is always shining on the good and the bad; it doesn’t discriminate. The host of a tea ceremony should aim to be the same, being gracious and non-discriminatory.

Living without Really Living

How did you first get into tea and tea culture?

I used to be an architecture student and was particularly interested in the tearoom. I was also curious why anyone, in the modern age, would practice this, because it felt like such an ancient tradition. The master/student relationship that is typical of tea culture and other traditional Japanese arts was also of interest to me.

What has your journey inside of it been like?

I would say a lot of it has been quite repetitive and boring to be honest. But there have been lots of small realizations, which combined and over time have made my day-to-day life much more colorful.

Now I appreciate a lot more shades of green in nature, whereas I used to only be aware of three (laughs).

As another example, before I began my tea practice I was not aware of the sensations of my feet as I walked. I would walk on all kinds of ground without being aware of the various textures of asphalt, stone, earth, wooden floors and so on. Now I am much more sensitive to the surface I walk on.

It is surprising how much potential my sensory organs have but I was looking without really looking. Likewise, I was listening without really listening, touching without really touching, living without really living.

What triggered this change?

Harmony, Respect, Purity & Tranquility

I think that this comes from the realization that I can be satisfied with less. I imagine that in 16th century Japan there was an abundance of wealth and ideas, as well as wars. There was this kind of obesity of wanting more and more.

So there was a counter-culture that took form at the time, which said that we can actually go the other direction and still find similar if not more satisfaction in our lives. Tea culture was born out of this counter-culture. It puts cultivating a certain quality of attention, and an appreciation of simplicity, connection and unpretentiousness at its core.

What have you learned along the way?

How does it inform your outlook on life?

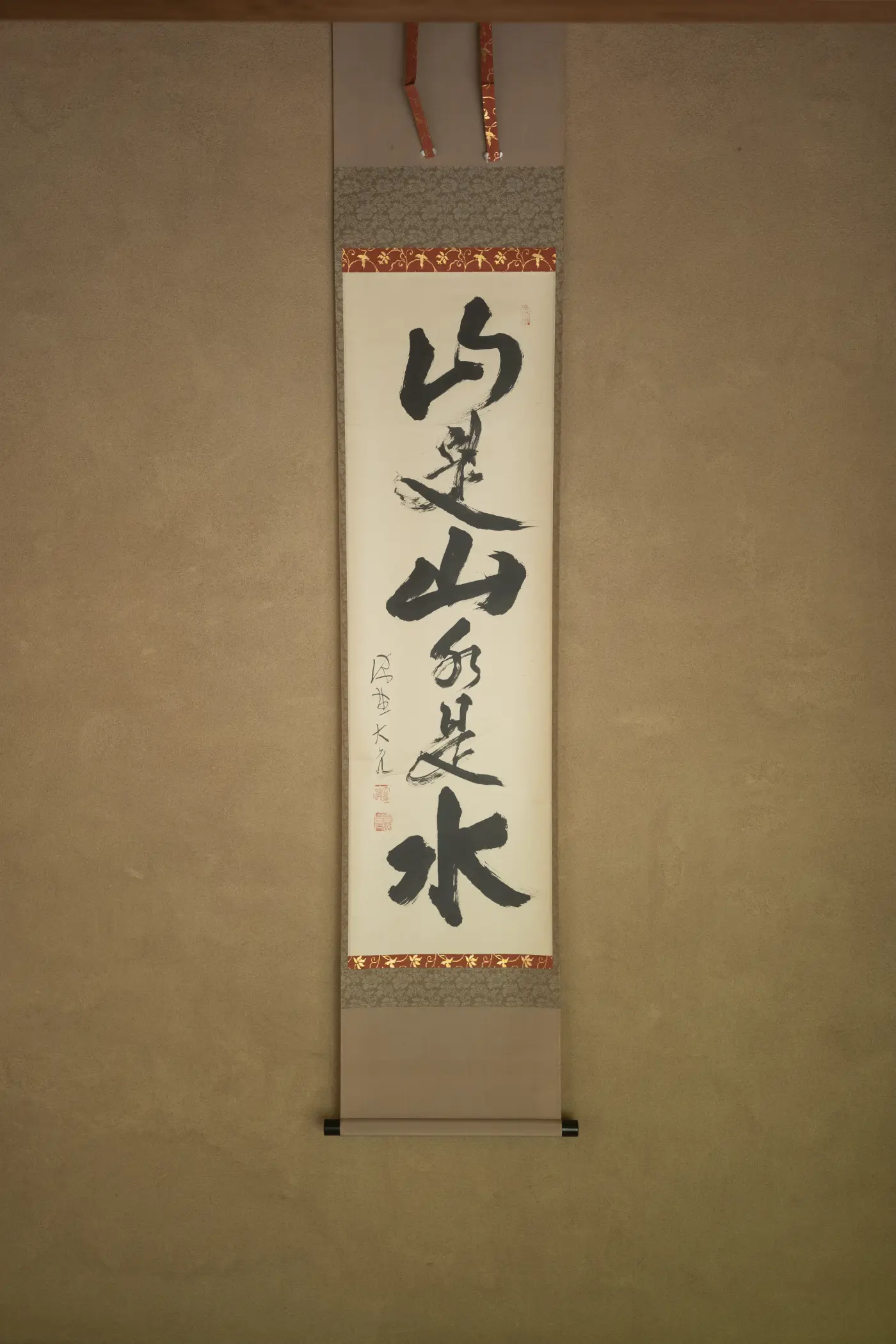

In the tea ceremony we talk about ‘wa’, which means harmony, ‘kei’ which means respect, ‘sei’ which means purity, and ‘jaku’ which means tranquility. ‘Wa Kei Sei Jaku’ (和敬清寂). It’s something that I have my own interpretation of, which was influenced by my own childhood growing up in different countries with many ways of thinking.

Originally, I thought ‘wakeiseijaku’ was referring to something outward, as they would often say, ‘be in harmony with nature’, to which I thought must refer to the environment. Another example was ‘kei’, which meant that I needed to have respect for outward things, like your teacher or the utensils. So for a long time I felt it was a ‘you vs the outside’ scenario.

However now I have come to understand that it is ‘you vs you’. Respecting yourself and coming to be in harmony with your own nature. Of course, for purity (sei) it means keeping yourself clean both physically and mentally, and for tranquility (jaku) it means having awareness of yourself, being self-aware.

In the practice of tea ceremony, we often are allowed to select the utensils that we like, so obviously you gravitate to the things with aspects that you like, such as texture and so on. But we are also told that we should include some utensils that we don’t like, in case our guests may appreciate them, even if we do not.

So there is a practice of harmonizing both things that you like and do not like in the tea ceremony. This practice can help you understand that contradicting things can coexist within the same system, in this case a tea ceremony, but in a wider case within yourself. That’s what we call Yin and Yang or the harmonious blending of heaven and earth.

What inspired you to create your own tea house and a more contemporary approach?

A Shared Experience Beyond Words

I was inspired by my teacher who has created his own tea house. He told me it’s important to have a place of practice and try to be independent.

At the moment I’m trying to make a sauna pod in my garden, because I learned that the samurai lords during the warring states period would enjoy their tea gatherings with a sauna. So I’m trying to recreate this experience for my visitors.

A lot of artists come in and out of this house and we often do collaboration work.

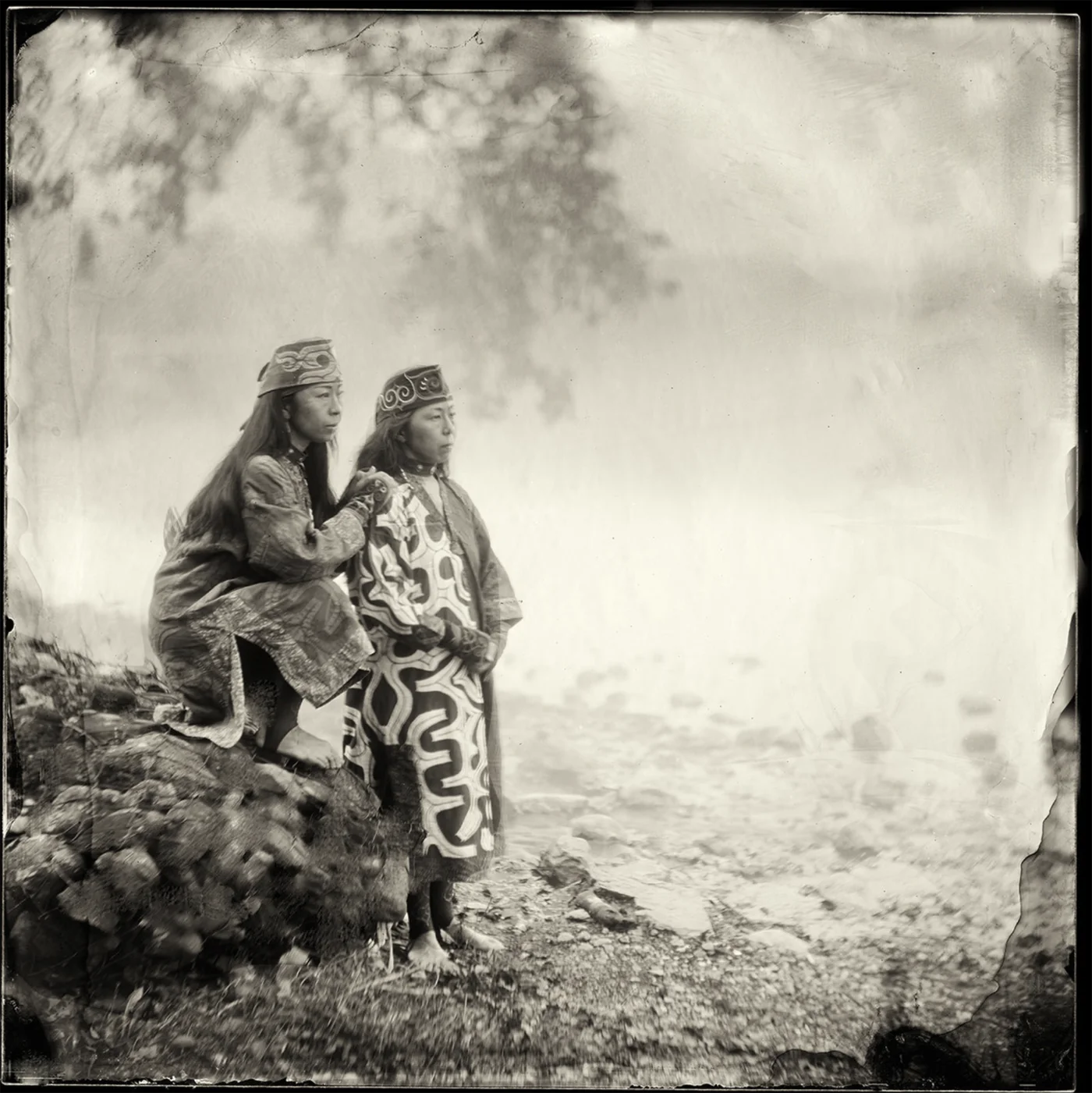

Sometimes I don’t serve matcha tea but instead we have experimental performances or installations. We can still call it a tea ceremony since we’re trying to create a harmonious relationship out of various disparate elements and that is the essence of the tea ceremony.

What is important to you when you relate to your guests?

I think we generally tend to over rely on words for communication, which is ok, but to me it is important for us to have a shared experience that goes beyond verbal communication.

For example, if we are in the rain together, or eating the same food, or looking at the same scenery, words are not needed. I think that when we are able to enjoy things beyond needing words, then that approaches my ideal of a harmonious relationship between host and guest.

Both Zen and Shinto are of deep interest to you, and you practice regularly in both traditions. How does each inform your perspective on life?

Emptying Our Cup

Zen came from ancient China and is said to have its roots in Daoism, which essentially is about living in the flow.

One day I was looking out at the trees in my garden. Suddenly a gust of wind made all the trees sway in sync as if they were one with the wind. So I opened all the windows and swayed with the wind as well.

The wind is a metaphor for all life happenings that come forth. We can sway along, letting it come and go.

Shinto is a Japanese religious practice which is deeply connected to agriculture.

In Spring we prepare for the planting of the rice. In late Autumn we harvest the rice. The tasks are in accordance with the seasons.

Both practices are connected with nature, and these perspectives were somewhat lacking in me, given they are not taught in schools, which are very human-centric. As a result, we tend to have a one-sided way of thinking of things.

How would you explain Zen to a complete novice?

Well, consider now that my cup is empty. Because it is empty, I have more choices. I can fill it with whatever drinks I want. But if it’s full of say apple juice, that’s all I can have.

So we say that our mind is like a cup, but it has a tendency to become full all the time, because we fill it up with the illusions of the future and the past, which cause us to miss out on all the possibilities of the here and now.

The Zen practice is to empty our filled cup so that we can be open and receptive, what is sometimes called ‘beginner’s mind’.

Experiencing Simple Things to the Fullest

How about Shinto?

How does it inform your understanding of tea and perspective on life?

Shinto is to acknowledge the Yaoyorozu no Kami (八百万の神) – Eight Million Spirits that come in many forms ranging from the sun, the mountains, or even in rice.

Objects which have been in use for over 100 years can potentially be treated as KAMI, sacred spirits. That is why in tea we respect and take great care of our utensils because it potentially carries a KAMI.

It is also why we keep our surroundings clean because when a space is purified, KAMI will visit and stay.

What do you feel is the greatest gift the way of tea has to offer to contemporary practitioners?

In modern days, I feel that when we are consuming something, like eating, drinking or experiencing something, we are not experiencing it to our fullest.

For example, when we are having a drink, maybe we’re having a conversation or looking at our phone, so I’m not able to fully sense the temperature of the drink, the sensation of the cup, or the color, or how it makes me feel, and there are actually many subtle layers of the simple experience that you are missing out on.

I feel that tea ceremony is a way to experience these kinds of simple activities to the fullest, and I think that is something of value.

Could you say more?

A Daily Practice to Stabilize Ourselves

I had a chance to go to the US before and after the pandemic, and I noticed a lot of people talking about burnouts and anxiety and how to deal with that. People told me that when they burnout they would take a break, go on a retreat, but when they come back to work, they burn out again.

I feel that tea is a daily ritual to self-check, and it’s a way to stabilize or normalize ourselves before the situation becomes too dire.

Like cleaning our teeth everyday, the daily practice of tea involves steps to clean and tidy our physical and mental state. Similar to how we stretch to center our body, the process of making tea helps us to center our mind.

What does an average day look like for you?

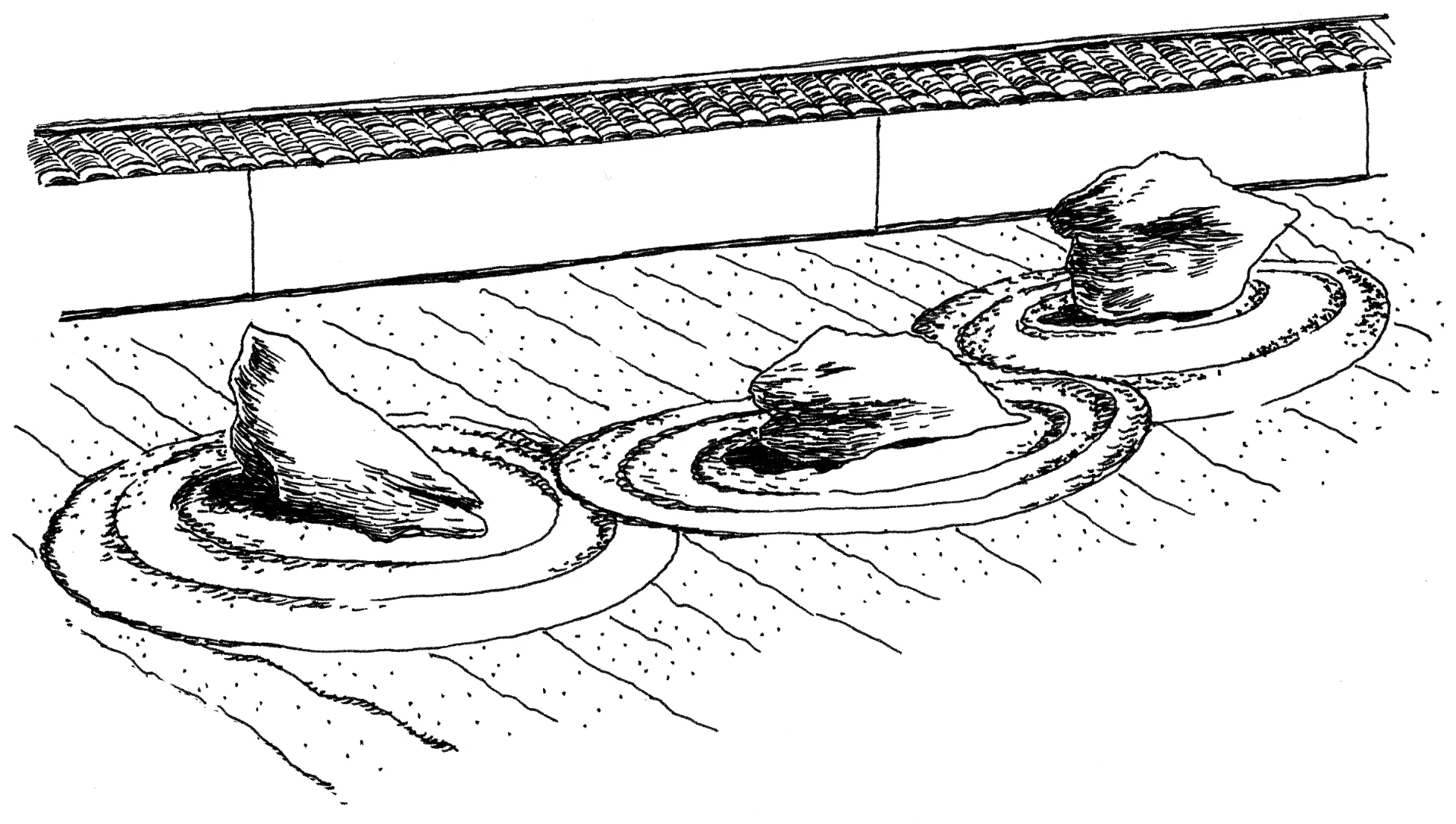

Because we have to prepare the tearoom, we do a lot of sweeping of the tatami and garden, it’s important to keep things clean. And then of course we sift the tea, heat the charcoal, and arrange the tokonoma display.

Each day is like starting from a blank sheet of paper. When the day ends, we clean up and it becomes an empty room again.

What are other sources of inspiration and curiosity in your life?

Heightening Our Sensitivity

Since I was an architectural student, I like beautiful design of course.

I’ve also always loved anime and still watch a lot. I find these subcultures very interesting as it’s a fantasy but still kind of rooted in reality.

Likewise, in the tearoom we are trying to make this dreamlike, extraordinary state, so I find anime quite inspiring.

Earlier you talked about wanting to find a master student relationship, did you

find it and can you elaborate?

Yes, I did. It’s comparable to a parent child relationship in that it is much more long term than a mere teacher/student relationship at school. Your schoolteacher is only your teacher for the hours that you’re at school but becoming a disciple is a lifetime commitment.

The phases are also very similar to a parent/child relationship. First the disciple will mimic the master, like a child will mimic the parent. But then the child will enter adolescence and start getting ideas of their own and go opposite to what their parents would say.

Eventually the child will leave home, like I departed my master after a while. However, once the disciple has his/her own students, they will find their way back to his own master with a new appreciation for what they did for them. Similar to how having your own children gives a whole new perspective on how your parents brought you up.

What is beauty to you?

We tend to think of beauty as something special to be found, whereas if you heighten your sensitivity, you’ll be able to experience different layers of things that are close at hand.