The Way Something Disappears

What would you say is the essence — the heart — of Okashimaru?

If I had to express it in one word, it would be “ephemeral.”

I was drawn to wagashi because each sweet has its own name, and within this little form contains its own world of seasons and stories. This is what initially sparked my interest to study wagashi.

For me, texture is especially important — or more so, the way something disappears.

Some say that my sweets feel very Zen, or that they sense the spirit of tea through them. This was never my intention, but it seems through making them I naturally came to embody aspects of tea and Zen.

People also sometimes tell me that when they ate my wagashi it reminded them of visiting festivals with their grandmother, or a particular season.

People often bring their own memories to my sweets. Those unintended responses are what I find most fascinating.

I think that’s true for art too. The works generate emotions from the viewers that the artist perhaps never envisioned.

The emotions and experience belong to the person experiencing it, not only to the maker.

Lingering Sensations

Could you share an example of how an encounter or inspiration becomes a wagashi for you?

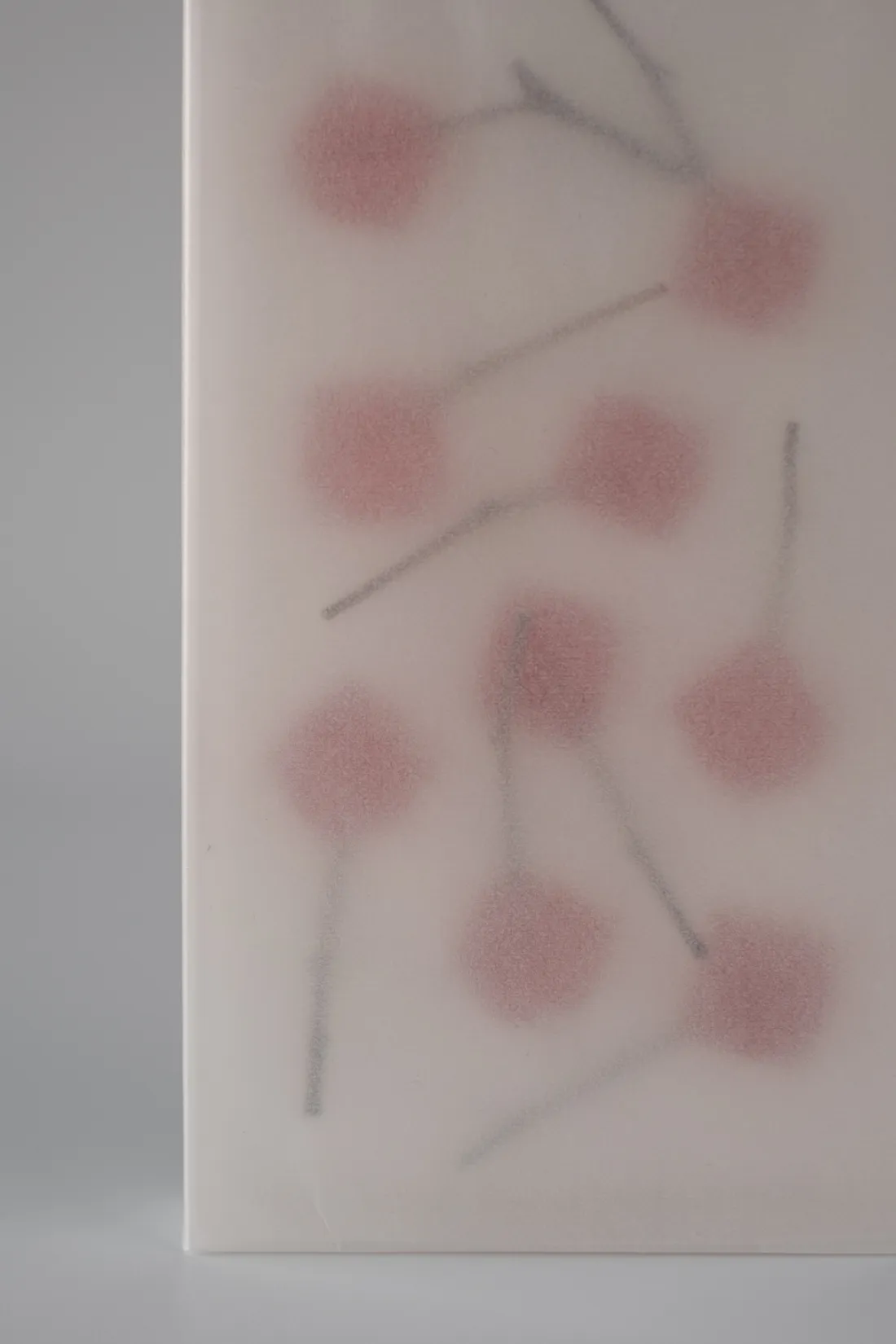

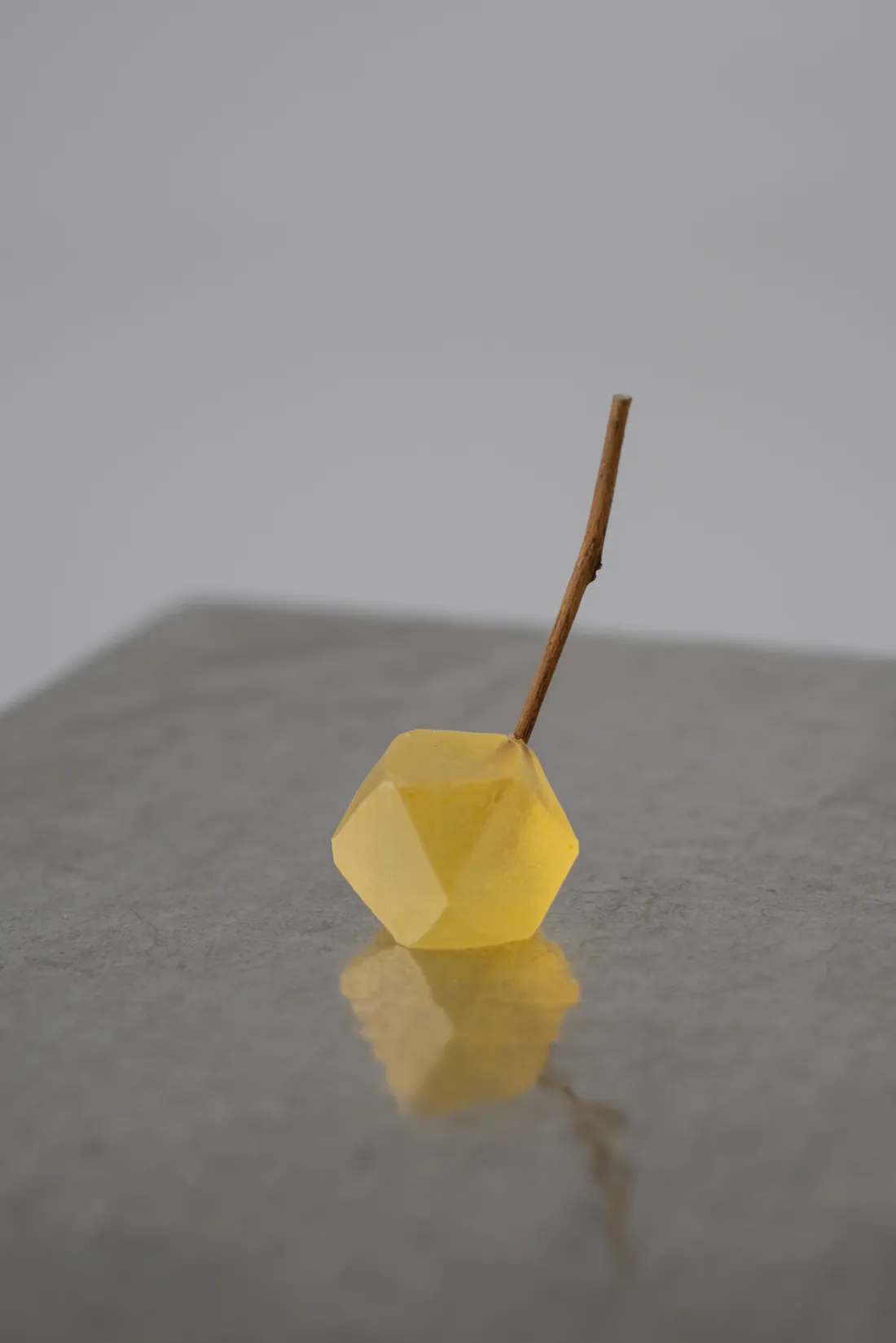

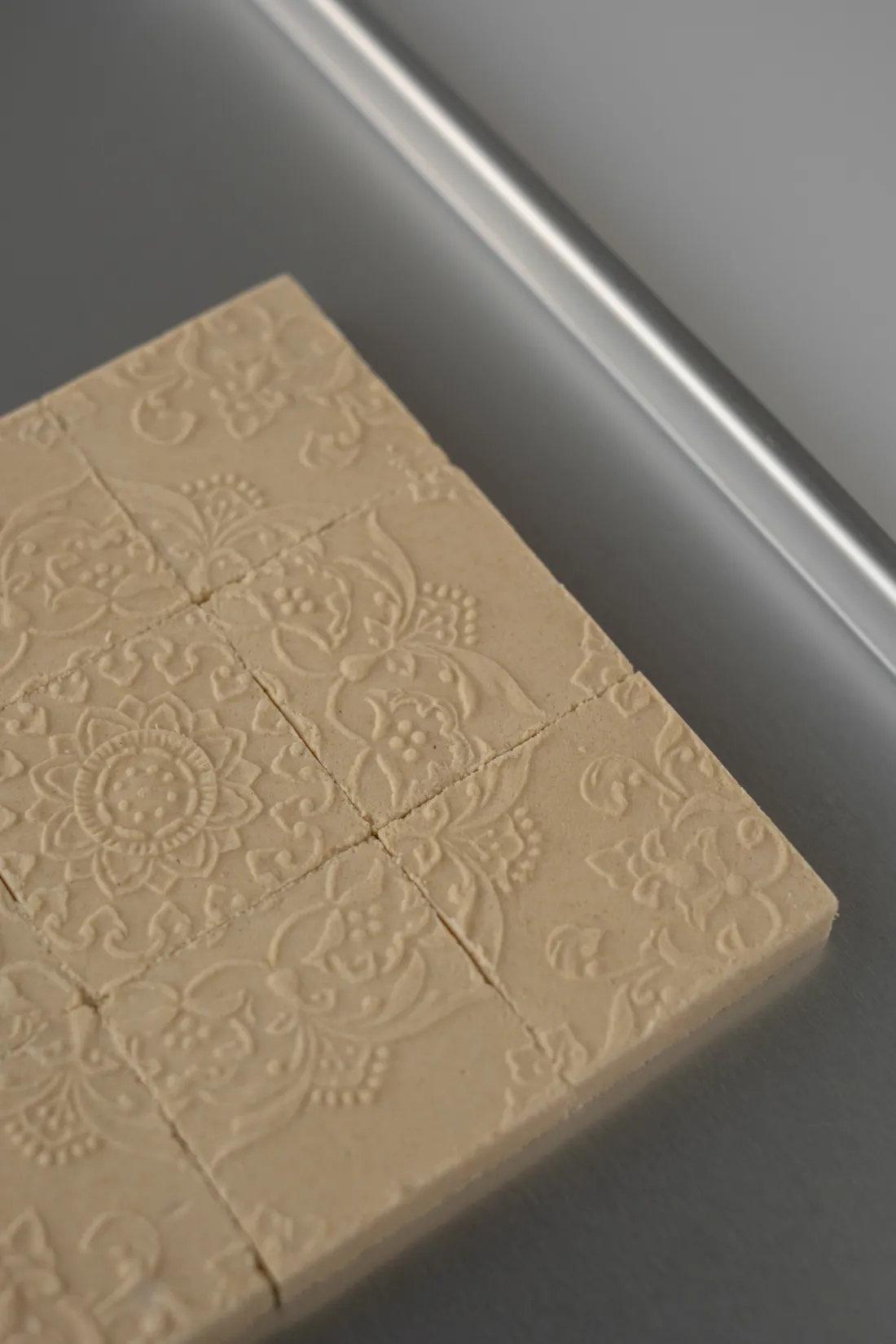

When I first encountered Islamic patterns in Morocco, I learned that in Islam one does not worship statues or idols, but rather patterns themselves. I was deeply struck by their power, and that encounter sparked a desire in me to create patterned wagashi.

I bought patterned molds there and began experimenting, but I quickly realized that using Islamic patterns directly felt strange. If I were to pursue this idea, it needed to be rooted in something Japanese.

At the center of the pattern I chose is a flower. It resembles a lotus, but it is not a real flower — it is an imaginary, fantastical one. Around it, grass spreads outward in a circular form, expanding like a ring and eventually disappearing. Because the pattern is grounded in Buddhist thought, it reflects the idea of reincarnation — the cycle of birth and death.

What matters most to me is the experience of disappearance itself. Not just visually as a pattern, but when a confection melts in the mouth and gradually fades away; that is the process that I want to express. It is this act of disappearing that I find most compelling.

My work, then, is to translate that experience of fading into sensation. I explored repeatedly how the moment of disappearance could be felt through taste and texture, refining it again and again until the sensation itself became clear.

In the final version, I added the fragrance of an-nin (almond kernel) so that scent would still linger even as the form dissolved.

Although it resembles a classic Japanese sweet called ‘wasanbon’, the flavor is entirely different. I value the moment when expectations are gently overturned, even though the technique itself remains traditional.

That gap between expectation and reality — that moment of “uragiri” betrayal of the senses — is important to me.

Uragiri – A Quiet Surprise

Do you intentionally include this sense of surprise — this gentle shift in expectation — in your sweets?

Yes — almost all of my sweets include that element.

I use the word uragiri, which literally means “betrayal,” though in English it may sound too strong. What I mean is something gentler — a small, unexpected shift that opens the senses. A quiet surprise.

That sense of play is where my ideas begin. When I create, I start with what I personally want to eat. If something I enjoy feels too sweet, I think about how to adjust it. If it feels like it needs just a little more fragrance, I consider how that might change the experience. From there, I add playfulness — what I think of as a playful heart.

This is how my ideas emerge.

This sense of playfulness feels closely connected to Zen and tea practice. Does that resonate with you?

Yes, it resonates deeply.

I want people to notice the beauty that exists in everyday life — to realize that something interesting is always happening, even within the most ordinary moments.

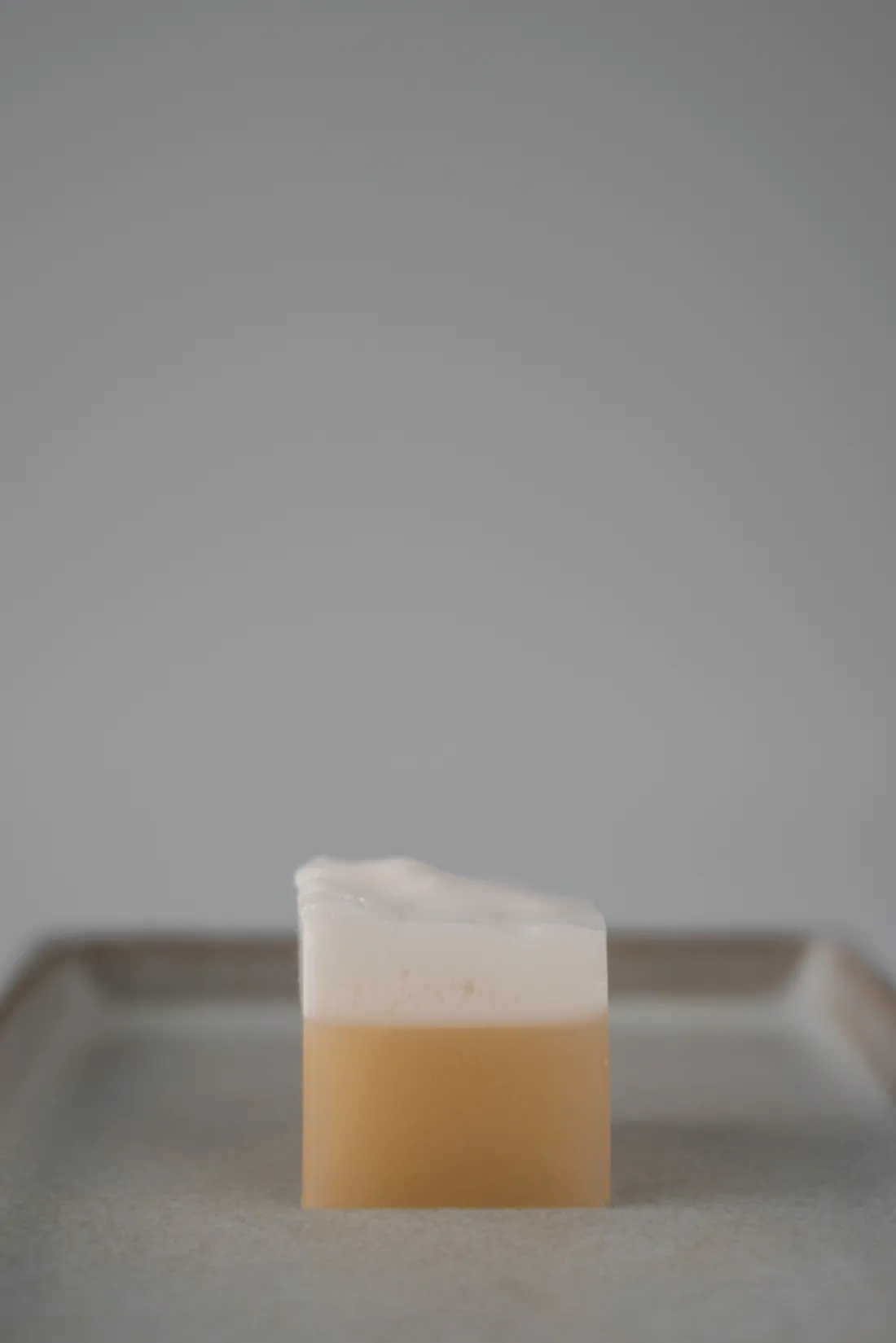

This sweet is called Kareha – fallen leaves. It was inspired by dried leaves in the autumn. I love the sensation of stepping on dry leaves — the crunching sound they make. I wanted to create a wagashi that recreates that joyous sensation.

It’s made from sweet potato, sugar, and rice flour, rolled very thin and baked. As you eat it, I hope the sensations of autumn emerge — the sound, the texture, the feeling of the season — and that it brings you fully into the present moment.

Being Moved by Small Things

How do technique, material and idea come together in your creative process?

I think it’s the same with any kind of craft. Creation emerges when technique and ideas meet and begin to respond to one another.

There is a constant exchange between concept, material, and skill — like a game of catch — where each element must listen and adjust. What matters is the balance that forms between them.

When you look back on your childhood, what feels most present to you now?

I grew up in Ise City, in Mie Prefecture. I don’t remember many concrete details, but what stays with me is an overall sense of happiness — my childhood felt joyful.

Even now, I remember being moved by very small things. On winter mornings, for instance, when you breathe out and your breath becomes visible, moments like that left a deep impression on me.

I was given remarkable freedom. There were very few rules about what I could or couldn’t do. I was allowed to explore and follow what interested me.

An Open Question

Was this awareness of appearing and disappearing already present for you as a child?

Yes. I was drawn to food precisely because it disappears when it is eaten. Even before that, I sensed something similar in music — it has no form, and yet it exists only briefly, before fading away.

What fascinates me is not the object itself, but this phenomenon of appearing and vanishing. I’ve never been especially attached to things, or even to myself, and that sensibility is deeply connected to how I think about life and death.

There is one question that continues to stay with me, and that I still don’t have an answer to: has something truly disappeared?

Sometimes customers say to me that although the wagashi physically disappears once it is eaten, it remains vividly in their memory — as if it continues to drift somewhere. In the same way, when a person dies, the body disappears, but is that person really gone?

I don’t yet have a clear answer to this question, and for me it remains open.

When did you first begin to feel that making would become part of your life?

I studied linguistics at university — though to be honest, I didn’t attend very often. While I was there, I became interested in photography and joined the photography club. That was when I first began to think deeply about expression itself.

Even so, I never consciously thought, “I want to be an artist.” Even now, I don’t really feel that I am making art. Sweets, and wagashi in particular, are not generally categorized as art, and being called an artist feels a little strange to me. Being called a craftsperson also feels slightly off.

I don’t feel the need to define what I make. I prefer to let its meaning arise in the encounter between the wagashi and the person who receives it.

Something Truly Meaningful

How did you come to choose wagashi as your form of expression?

After graduating from university in 2006, I began working at a wagashi shop. I joined with the hope of becoming a craftsperson, but at the time it wasn’t an environment where women were expected to make wagashi. Instead, I worked as a salesperson.

My desire to make sweets never left me.

During that time, there were wagashi I felt compelled to make — things I wanted to express for myself. So alongside my work as a salesperson, I began making wagashi on my days off and after work.

At first, it was simply a personal practice, something like a hobby or a side job. I never imagined it would become my profession. But little by little, it did.

What role do relationships and collaboration play in how you create?

There are limits to what one person can achieve alone.

When each person contributes their role and those roles overlap, something truly meaningful can be created.

I’ve never felt the need to do everything by myself. I’ve always been interested in working with others.

Are there artists or makers whose way of seeing deeply resonates with you?

There is a painter named Maruyama Naofumi. His paintings draw me into another world, and his way of expression deeply resonates with what I aim to convey through my sweets.

Keeping Excitement Alive

Where does inspiration tend to come from for you?

Everything can become a source of inspiration.

I actively visit museums, and enjoy eating different foods, but in the end I don’t know what will spark inspiration. I am often surprised, and the most unassuming experiences become the hint for a new wagashi. That unpredictability is what keeps it interesting.

One thing I can say for sure is, if my heart isn’t moved, creation doesn’t happen. Keeping that excitement alive is essential.

In today’s world, is there something you hope your work might gently shift for people?

We are now very much dominated by an internet-based society. However, even in this established virtual society, food remains a physical experience.

Engaging the five senses through food still holds deep value. But food is still something you can’t experience through a screen. That’s why food still has great potential.

If it becomes a reason for someone to step outside or go somewhere, that would be wonderful. Experiencing things with all five senses is very important to me.

The simple act of feeling the breeze on your skin, or something small, just being in nature — it’s really important.

The world of food is a medium that connects, and brings people together.

Becoming Something Naturally

As we close, is there a final reflection or message you’d like to share?

I believe it’s important not to categorize or aim for outcomes. Becoming something naturally matters more than trying to express it.

For example, I don’t study Zen to express Zen. I feel that I become Zen as a result. It is not about setting something as a goal, but rather building up the mind.

I try to carefully collect what matters to me, one by one. Then I look at how those things come together. I gather what is meaningful to me piece by piece, and reflect on what they form as a whole.