Cutting Through The Noise

What would you say is the essential value of Zen in today’s world?

Toryo Ito: Zen itself is a process. It’s the action of cutting through the noise that surrounds us to uncover what is important in life. To rediscover the possibilities that surround us but have become buried or invisible in our oversaturated daily lives.

It’s like putting on a different lens or shifting your point of view so that you can once again see the truth and potential of life. In Zen, when you drill down to the essence of an issue, you’ll suddenly discover possibilities where you didn’t see any before, finding potential in what seemed hopeless. In this way, we can incorporate Zen into our daily lives, as well as in the work we do.

How do you drill down to the essence of something?

Question Everything

At the heart of Zen lies the practice of questioning every belief that has entered your mind, examining it deeply through meditation and inquiry, and then extracting from it what is true to you. And you don’t finish by checking it once. You check on the truth every day. You keep re-evaluating your beliefs.

This can be a strict way to live, the polar opposite of what conventional religion dictates, where you are expected to accept everything you are told without question. In Zen, you are told to question everything.

That sounds quite tough. Don’t you feel like you are losing your sense of self?

I understand this may sound quite tough. But in my experience, this way of thinking actually gives you a constant fresh perspective, so you could also say it’s always fun.

Could you give us an example?

Daigi: Great Doubt & Radical Curiosity

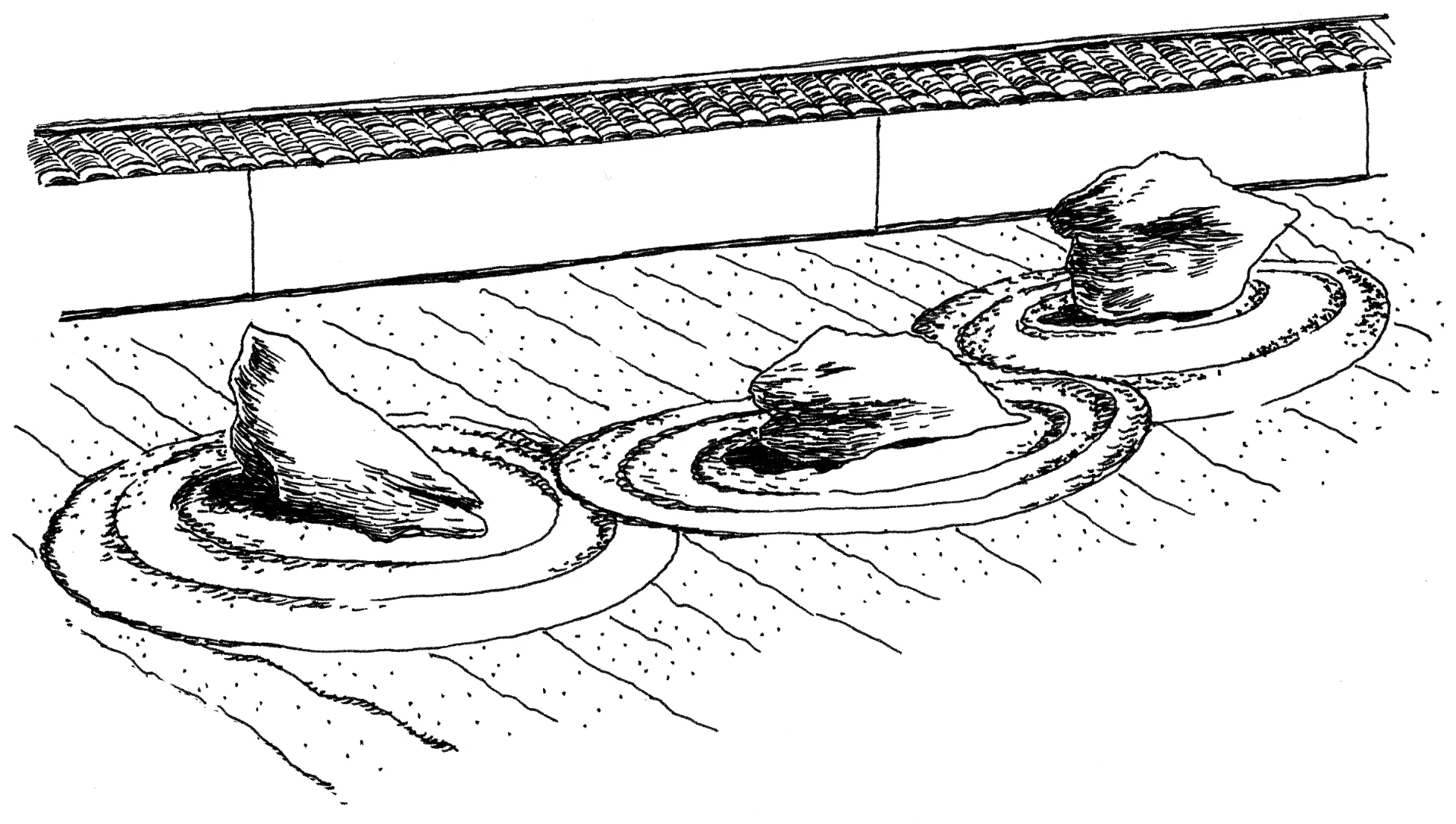

Of course. At the temple, we often serve and drink tea with guests. If we don’t question the process, we tend to simply follow the forms habitually. This results in the usual way of how things have been done for many centuries. There is comfort there, but no freshness.

So instead, I might wonder whether there really is only one way to use tea ceremony tools. I start trying things out, like whether it would be more appropriate to use a saucer upside down as the lid instead. In Japanese, we sometimes call this process of re-discovery or re-imagining ‘mitate’; to look with fresh eyes to find new ways to use things.

When you question the defined possibilities of everything, it opens up a new way of seeing that is filled with discovery, curiosity, wonder and positive doubt.

Is there a word for this kind of positive doubt?

I: In Zen language, it’s called Daigi (大疑), which literally means Great Doubt or Big Questioning. It might actually be the most important concept in Zen. If you practice Zen, you carry this doubt with you everywhere.

Everyone, including you, me, and the reader, has biases. There’s nothing wrong with having them, but it’s important not to become limited by these beliefs. If we hold them too tightly, our view of the world and ourselves narrows. It loses its vitality and potential.

If you define things too rigidly you actually cannot see the dynamism and freshness of the present moment clearly anymore. This applies to things, people, and concepts. Questioning your biases is the very foundation of zen. It’s also the doorway to being at choice and experiencing freedom.

Could you say more?

You Always Have a Choice

Sure. Ultimately, freedom is something that evolves from within yourself. True freedom exists when you believe you are free, when you recognize that you are in control of what you are going to do. Freedom exists the moment you realize you have a choice.

Even when you are in jail, you still have choices, limited though they may be. And people are spoiled for choice now. But when your head is overflowing with thoughts and concerns, you may not be aware of the options at your disposal.

So the first step is to realize you have a choice, and once you do, to come up with one more option, one more thing you can choose.

People lose sight of these things when they are worried or anxious. They worry about whether to go to the office or whether to quit. Only seeing things in black and white, either or, should I or should I not. I believe there is always a third option besides the “should I or should I not”.

Breaking through this narrow field of black and white vision enables you to see things more clearly, in full color. From there you can uncover one more choice. That is zen in practice. You realize you have a choice, you come up with one more option, and then you make a decision what to do.

Only then are you the one in control of the decision, and can you be held accountable for everything that follows from that point. Rather than shifting the blame for that decision on your circumstances or on someone else. This process is real freedom.

Your True Self is the Protagonist of Your Life

This reminds me of a Zen word I wanted to ask you about, Shujinko (主人公) . These days it’s often translated as ‘protagonist’, but in Zen its original meaning is ‘true self’.

Is it connected to what you were just talking about?

Yes, it is. The only way to be your own master is to be aware of the choices you make and to feel that you are actually the one making the decisions. Unhindered by your own limiting beliefs and biases, as well as those imposed upon you by others and society.

However, the word protagonist evokes the idea of being a central character in a story, or the hero from a tragic story. If you start thinking that your life is not worth living unless you’re in the center of the universe, then you’re completely missing the point.

Just Being You is Enough

In the current age of social media, with its celebrity and influencer culture, people have become obsessed with the notion of being the lead character in life. I think this is misguided and creates a lot of suffering.

The truth is that we are all cut from the same cloth. Accepting our ordinariness in this way can be liberating. You don’t have to become someone special to be important. There is no need to be “number one” or “the only one”. These concepts don’t really matter.

If you place too much importance on them, you will only become obsessed with the fact that you’re not unique enough. It would be better if we could do away with all that, and be content being our own master. That is enough.

I’m fine with just being myself, just an ordinary person. I believe it’s okay to worry about the same issues that have occupied humanity for the past 2000 years. However, it would be nice if we could borrow the wisdom of our predecessors and add something to it, even if it only amounted to 0.1%.

I agree, but making that shift seems easier said than done.

Do you have any tips for how to do that?

Can and Need vs. Want and Like

A different way to look at it is to say that today’s culture seems to encourage us to first focus on what we “Want” and “Like”. Our desires and preferences are given center stage.

Whereas I believe it’s more important and helpful to first focus on “Can” and “Need”. “Can” being what you can do and “Need” being what people or society need you to do.

When you have a clear view of the things you can do and the need others have for it, you are able to see how your “can” and the world’s “need” are related to each other and can meet. In that way even if you respond to a “need” with some personal doubt as to whether you can actually do it, if you examine this limiting belief, it will likely lead you to new personal growth.

If you then add “want” to this and find something that matches all these three requirements, you have found your vocation. But you should start with “can” and add “want” at the end – if you start off focusing on “want”, you lose track of what is important from a larger perspective.

Let me give you a personal example:

I always thought I’m terrible at public speaking. So in order to improve this competence, to be able to say that I “can” speak in public, I began organizing zazenkai (zen meetings with instructions or a short talk). Before I knew it I was speaking in public every day of the year. Once my “can” had been completed, I could focus on “need”, for example the “need” for these types of gatherings for companies or for individuals. And now I find myself “wanting” to speak about certain topics to cater to the different needs.

Even though I wasn’t focused on developing my uniqueness, I did end up coming up with a way to speak that is my own, that people outside myself might call unique to me. This all came from me searching for something I “can” do and then looking for how this could serve a “need”.

In this way, the process of helping others becomes its own reward, without any concerns about your individuality.

How can we begin to incorporate meditation into our daily life?

Bringing Meditation into Your Daily Life

One way is to make time in your life for sitting meditation. This can be at home, with a group, or at a temple like mine. But for many people this is something to add to their already full lives and they may find it difficult to fit into their schedules.

So what I recommend is to bring meditative awareness as you perform everyday, mundane tasks. Things that you do every day anyway, without being asked to do so.

It can be cooking or any everyday activity. As you perform these tasks, pay attention to your senses. You can loosen your stance and observe things for a while without judging. It is a way to switch daily activity into meditation.

The idea is to let go of any judgment or preconceptions and observe how that makes you feel. If you can do that, you’re meditating. The entire task becomes your meditation exercise.

It’s important to be attuned to all your senses in everything you do, without judgment, even the things that don’t go well. Just accept the way things turn out, observe the results, observe what effect it has on you. There isn’t a right way to observe these things, it is more like taking a step back and looking at yourself.

So when things go badly we should just take a step back and observe?

Perhaps a more precise way to say it is to try being conscious and present while performing everyday tasks and creating time to observe your thoughts and feelings. The mundane task then becomes a meditation exercise.

It’s hard to simply flip the switch to meditative mode when something negative or impactful happens. That takes a bit of practice, so it’s best to start with neutral mundane activities you do anyway and that don’t carry a lot of emotional intensity.

Like walking to work. If you do this every day, you’re not focused on whether you’re walking well or if you’re doing something wrong, and this opens up the room to simply observe yourself as you walk.

Or, if you take the train to work, you can use your five senses to observe your posture or your breathing. You can make use of those moments every day, while performing chores.

Perhaps the easiest way is if you make use of the time when you’re drinking coffee or tea. You can observe the texture of the cup, your posture, the tension going out of your body, the aroma that floats up when you bring the cup to your lips, the taste, how the liquid moves in the cup. Observe what thoughts come up.

Don’t try to control the process, just observe as it unfolds.

Thank you so much!

Any final thoughts or invitation to the reader?

In the end, I think it comes down to seeing things clearly. It’s a process of questioning what you have been told, re-evaluating the world around you and using this to uncover new possibilities.

Zen is about discovering the truth again and again.