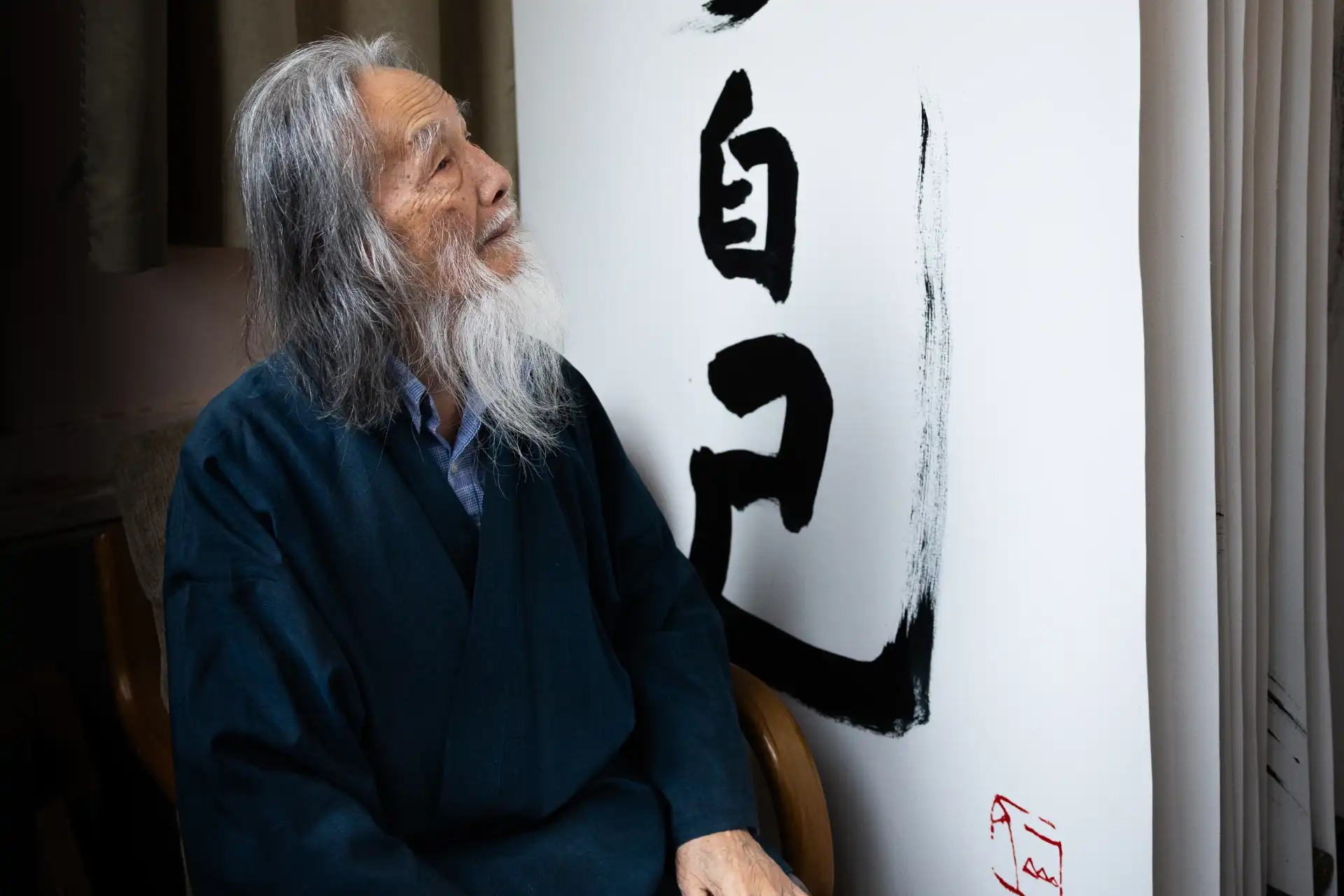

It is Not About You

Before you became a Zen monk you worked in the field of craft.

What was it about the world of craftsmanship that drew you in?

I worked in the advertising department of a local Kyoto newspaper. At that time, I visited all kinds of companies in Kyoto. I saw the beauty in the world of handcrafts that had existed and continued for such a long time. So, I wanted to learn more about that beautiful way of life.

That’s why I left the newspaper and started a new career as a producer for traditional crafts. It allowed me to work with many different types of craftsmen.

What was the deeper beauty or spiritual stance there that moved you initially?

In the field of craftsmanship, it is not about you. It is not about how you want to stand out from the rest or make a name for yourself based on such and such criteria. There are craftspeople like that too, but essentially, it’s about passing on the technique and knowledge. So you have already detached yourself from yourself.

You throw away your ego. While carrying on craftsmanship and innovating it, you pass on the aesthetic sense that has been refined over many years to the next generation. It is about continuity. This resonated with me deeply.

Reverence for Nature

Are there other ways Zen and the spirit of craftsmanship connect for you?

In the end, whether you’re in traditional crafts or arts, your creations ultimately end up resembling the beauty of nature. At least that’s my impression.

Craftspeople intuitively understand the limitations of human beings and have a reverence for nature. Yet they endeavor to make objects as best as human beings can do. There is a sense of humility in that.

That shares the similar essence as Zen; that we’re one with nature. I think this is what connects both worlds.

And that is why I came to Zen. Because I felt that Zen touched the very core of that philosophy.

Seeing without Biases

How would you describe the essence of Zen?

Zen is about the way you perceive and experience the world. It invites you to inquire deeply into the true nature of the world you live in and who you are.

It’s not so much a way of thinking, but rather a way to see reality as it is. To experience the present moment just as it is. Zen invites us to see without any biases.

The ultimate goal is to understand that you and the world are one, and to get a sense of it with your physical body. Through such an experience, you will know that you are ultimately free. That leads to a fundamental peace of mind that transcends life and death.

Zen offers techniques to support you in that process, but it doesn’t automatically take you to a goal even if you rationally understand it. You have to see with your own eyes, feel with your own body, interpret the reality for yourself, and come to your own understanding.

It is a deeply personal path, where you have the ultimate freedom to choose your answers, as well as the process of getting to them.

“The ultimate goal is to understand that you and the world are one.”

Do you remember the moment when you experienced that freedom?

I don’t think it was a moment. Rather, it was a gradual accumulation of both subtle and eye-opening shifts in awareness that I found throughout everyday life, seated meditation called ‘zazen’, and by training at the monastery.

Through this gradual process, a sense of deep knowing that I had as a child was gradually confirmed. I could feel its assurance installed in my body. At the same time, what feels a bit mysterious is that I felt what I knew about this world as a child was now validated based on logic.

Could you say more?

Empty of Belief

As we grow up, we naturally acquire a lot of information and concepts to make sense of things. Over time these become filters for how we see the world. Helpful in many ways, but also limiting in others.

Simultaneously, we tend to suppress what we thought and felt as children. As a result, we gradually lose this free and direct way of experiencing and interacting with the world.

Zen should allow you to rediscover and reconnect with this deeper sense of aliveness and potential that you experienced as a child. Restoring in you the freedom to meet each moment with more openness and wonder.

This ability to meet the present moment with openness and spontaneity is valued and cultivated in Zen.

It requires us to cut through our habitual and fixed way of seeing, and see the world as it is. Free from any biases and judgements of right and wrong. The primary technique Zen offers to do this, is through seated meditation or‘zazen’.

What does ‘zazen’ entail?

What I think is special about zazen is that you only have to stop and observe reality as it is.

There’s no special technique or fixed ritual. There’s no faith that you have to have. That’s why it doesn’t conflict with other ideas and religions. Since all you do is stop and observe, no one can stop you from doing that, right?

And the object of observation is reality. It’s the reality around you and the reality that is you. Anyone can do it anytime, anywhere, and all you have to do is stop and sit down.

Being Part of Nature

What is the core insight you hope people realize through Zen?

The most essential message that I want to convey is that human beings are part of nature. If we re-discover that truth, then it will set us free.

It may sound a little far-fetched, but you are the world and the world is you. Everything mutually affects every other thing. Everything exists in a web of connection. This is the message I would like to convey.

If you can experience this core truth of interconnectedness, it means that feelings of separation or not being good enough do not actually exist. They are without substance and based on the illusion of separateness.

In modern society we are very in touch with our separateness and individuality and as a result, we tend to forget this simple fact of our nature as human beings. Namely, that we too are a part of nature.

When we see ourselves as being separated from nature, I believe it is a state of being blind and not seeing the reality as it is.

The boundary between inside and outside, self and other, human and nature, gradually dissolves as we move deeper into Zen.

I want to deliver the message not by words, but through the sensory experience as if you’ve tasted it before. Through Zazen.

Not just with the head.

Exactly. Real understanding happens through direct experience. It can start with a rational understanding, but it only becomes alive and embodied through your direct experience.

For example, even if someone explained the taste of an apple, you wouldn’t understand or know it. No matter how many books you read, you would not know what an apple tastes like.

But if you had eaten an apple before, even once, then you would know THAT taste and no other words are necessary. That’s the real knowing through your senses. I want people to get that level of understanding.

Through such an experience, you can be sure that you are part of nature, and the sense of ease and acceptance we talked about earlier on will come. But it will not come through your head, but through your senses.

Welcoming what Arises

So how do we “taste” Zazen to arrive at that solid knowing?

Through observation. That is the primary technique of zazen.

I use the word “observation” but I don’t only mean actively looking, feeling or thinking. I use it in a broader sense: it can be surrendering to the present. It actually works by just passively perceiving your surroundings and what arises in the moment. It can take any form as long as you are not falling asleep. That is what I think.

That sounds wonderful, but also hard to actually do.

What would you tell someone who feels they don’t know how to do that?

I would tell them to just stop and be still.

Observe. Think whatever you want. Feel whatever you like. If you don’t like to think, then of course you can try to stop thinking. Just put yourself right here and now, and take a moment to savor the reality.

So you observe yourself just as you are in this moment.

You can observe objectively, or you can try feeling it subjectively. You can go back and forth between the two. Even something like, “My feet hurt!” is an object of observation. The pain is also an object of observation, and how one’s feelings are shaken by the pain. Or the urge to untie one’s legs is also an object of observation.

All our unconscious beliefs or habitual tendencies will show up and become noticeable as we slow down and pay attention. It allows you to become more aware. With practice we can choose whether to go along with them or simply observe them without acting on them. This is another way that over time zazen offers us more freedom.

Understanding Things Experientially

It seems natural to want to avoid discomfort.

What’s the benefit of not doing that in zazen?

It depends on what you want to do.

Let’s take the example of your legs hurting while you are seated in meditation and the urge that arises in you to change position or do something about it. If you want to keep on doing that every time your leg pain comes up, you can of course do that.

But if you don’t want to be disturbed by the pain every time it shows up, then you should try to observe what would happen if you left this pain alone.

Then you’ll notice that after the initial disturbance and intensity of becoming aware of the pain and wanting to avoid it, you will know what will come. You start to feel a tingling sensation in your leg, then later it goes numb and you lose feeling sensation.

After repeating the process, we come to realize the maximum level of leg pain, but also understand that it disappears in this certain amount of time. You will experientially understand that your legs aren’t going to break as long as you untie your legs every hour, so the fear of the pain will disappear.

Next time you sit in zazen and the pain surfaces, you’re able to sit with peace of mind and not be shaken by it.

By moving through the actual experience with gentle awareness, we come to the realization that it’s okay to leave our initial fears and anxieties as they are and do nothing about it. This is very liberating and empowering.

Distraction as a Seed of Realization

That seems to apply to all kinds of real and imagined pains and stresses.

Yes, this is just one example of many stresses we learn to observe during Zazen. Anything that arises, whether it’s a sensation, a thought or an emotion can become an object of observation and an invitation to start your exploration.

It can be a mosquito flying around and what triggers inside of you, it can be a feeling of resentment you feel towards your boss or spouse, or a sense of anxiety around something in the future or the past.

It is important to see how your attention is scattered at first. In this way, each distraction is like a seed of realization.Through Zazen, you will pick up and explore them one by one.

Many of the participants in my in person and online zen classes tell me that they are able to express their feelings and communicate them to others much better as they now have a better, deeper understanding of it themselves.

You also hold Zazen sessions online.

Does it work just as well as doing it in person?

Absolutely. In fact, I hear from those who have been sitting together with me online for more than a year that they have seen genuine changes in themselves.

My conviction is that you don’t have to go all the way to train in a temple, and do Zazen all the time in isolation from the world. That of course is very powerful, but I believe that if we incorporate Zazen into our normal work and daily life, we can feel the changes in our lives and live more freely.

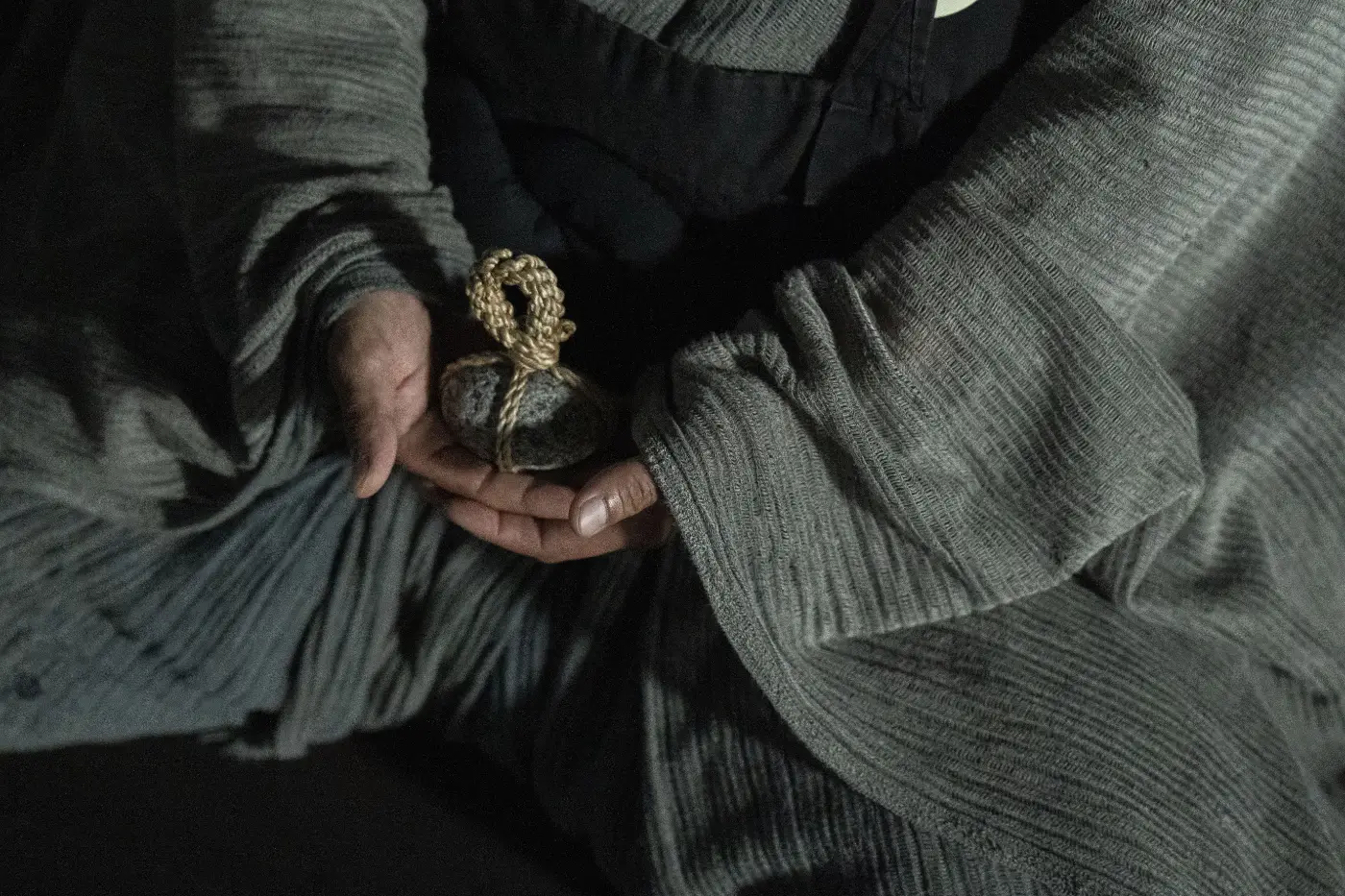

Craft as a physical vessel for spirituality is still part of your life. You make boundary stones, called ‘kekkai-stones’ in Japanese.

We All Share the Same Origin

What inspired you to make them?

People generally think Zen philosophy can be quite abstract and difficult to grasp, especially if we don’t experience or practice it.

So I thought it would be nice to also have something tangible to convey the idea behind Zen. I believe there is something one can only communicate through tangible objects. Having previously worked with a lot of craftspeople I think I understand the power of having a form.

What do you want to convey with them?

Kekkai, or boundary stones, were originally placed in the gardens of Zen temples or tea rooms. They served to prohibit entry beyond a certain point or to encourage people to pause and appreciate the surrounding landscape.

So they can offer an invitation to stop, be still and become aware.

The stones are wrapped with hemp rope that over time will untie, so the stone will return to just being a mere stone. I hope this conveys the idea of impermanence and that the boundaries we create do not actually exist from the first place, but they are concepts that we have invented.

In Zen philosophy, there is a notion that ‘heaven, earth and I all share the same origin, and are therefore one’. Also through Shinto, the ancient indigenous faith of Japan, the spirit of respect for nature and a desire to live in harmony with nature is deeply rooted in Japan.

I believe Zen and Shinto point to the same thing. It is this philosophy that I would love to share with many people.

I hope it will be an opportunity for many people to live with great peace of mind and freedom.