Always in Flux

You grew up in the countryside of Fukushima close to the forest.

How did growing up there shape your love of nature and outlook on life?

I felt like trees were my playmates. Growing up I observed the seasons change through those trees changing. In Spring they would bud, in Summer the leaves would fan out, in Autumn the leaves would fall, and in Winter they would dry up. I saw this cycle repeating very close to me every year. Not only for plants and trees, but also for living things.

I felt things in the forest were always being born and dying. This deeply imprinted in me the awareness that nature is always in flux. On the other hand the cycle itself remains the same. Things just move from one state to the other.

Before becoming a woodworker and artist, you worked for an Italian design company.

What did you learn there and what eventually made you decide to switch careers and start woodworking?

I used to work in a furniture company for ten years, handling things like corporate sales and so on. Of course, I learned many skills there related to business affairs, but I was also fortunate to be able to attend the biggest furniture trade show in the world, and there I could absorb details from many top designers, which I think contributed a lot to my education.

My company was a contemporary furniture manufacturer and thus the designs were very sharp and minimal, which still influences my work to this day. Being able to study the work of great designers as part of my previous work definitely contributed to my current work.

Then when the triple disaster hit Japan in 2011 it was such a huge shock and tragedy. It made me fundamentally question and reconsider the direction of my life. It was then that I decided to try and carve my own path and go back to school to study woodworking.

What was the experience like of going back to school at age 35 and learning to work with your own hands?

The Value of Handmade Things

I used to always like making things – as an elementary school student I made spoons and so on, but I never had the feeling that I could do it as a job. I always thought that making furniture required large organizations behind it – I thought you needed a designer, a factory, and a distributor to be able to function.

However, quitting my job and learning basic woodworking skills from the ground up caused me to realize how much you can do on your own if you try. I was honestly surprised. I also felt that trees are such an amazing resource – it simply grows back if you leave it, and being able to use simple techniques to make things for your life out of this resource is extremely interesting to me.

What do you feel is the value of handmade things in today’s world?

There’s a definitive difference between handmade and mass-produced processes. Carving things one by one tends to leave your own impression on the work, and in many cases this is intentional. This makes me feel a sense of responsibility and purpose in making products.

The head of the mingei movement, Soetsu Yanagi, said that machine-made things cannot convey the maker’s feelings and conscience in the way that handmade items can. In the same way, the craftsman’s conscience directly influences the things they craft in a way that gives them a special kind of attractiveness.

For me, when I make something, and I’m nearing completion, I wonder how far I need to perfect it until I’m satisfied. I realized that’s something only I can decide. It’s a decision based on simply wanting to make something beautiful, and whether it’s something I feel I can release into the world.

I feel that responsibility keenly whenever I make something, especially since I’m not working under anyone. So everything I make is because I want to make it. It is simply fun to make handmade things, and I think it is fun for people to use them too.

Not Seeking Control

Your work is characterized by its exquisite use of wood grain, seeming imperfections and elegant curves.

How do you seek out these qualities and what is important to you in the process of creation?

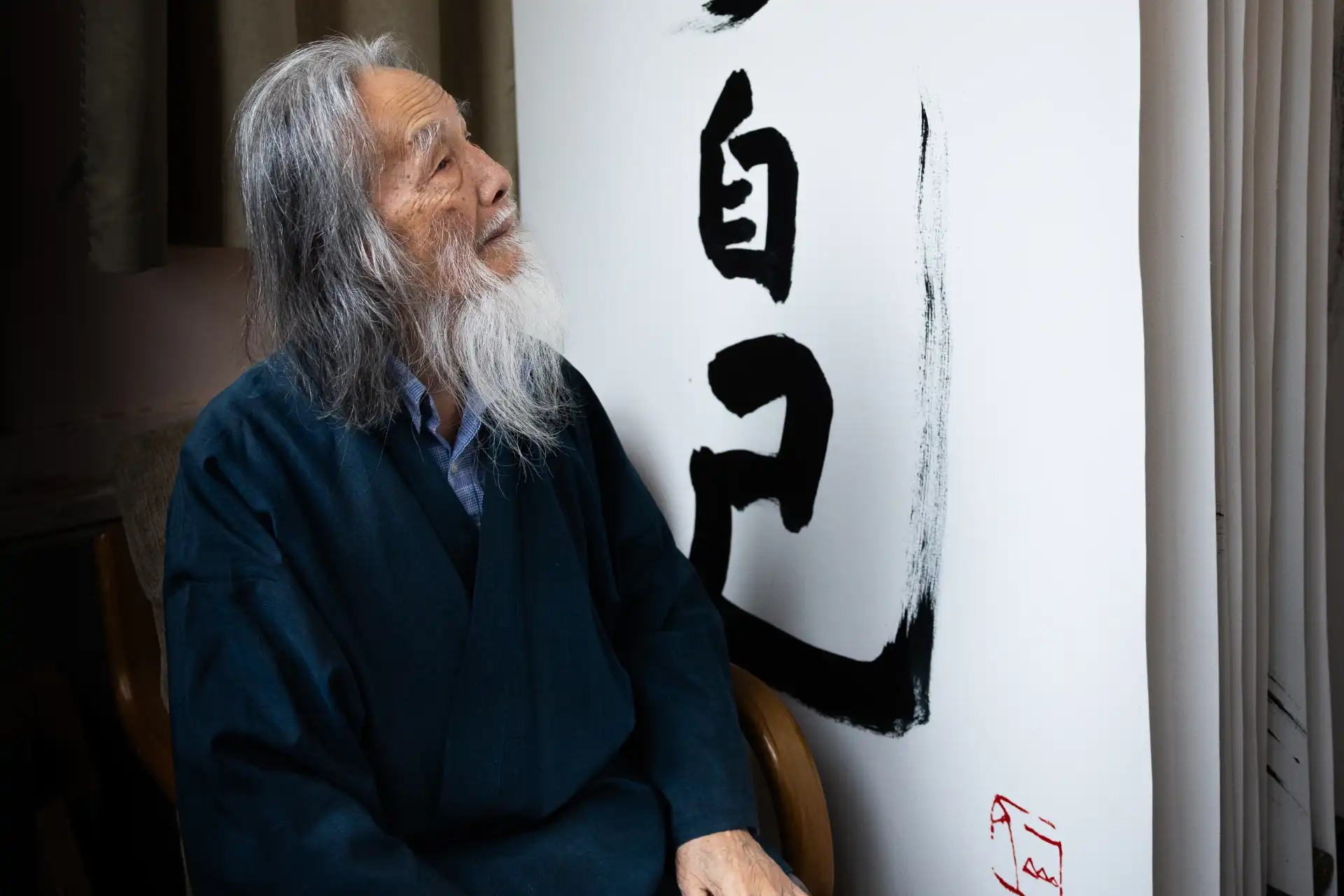

I’m never sure where my work fits on the spectrum of art versus product. In Japanese we call it ‘kogei’, which is things with utilitarian use but incorporating artistic elements.

As for what I do, I don’t seek to completely master my material in the fashion of some western styles of craftsmanship. Sometimes the wood has knots and cracks, which I let show. Perhaps incorporating these incidental accidents of nature does not fit neatly into the context of true art, however in a way I’m sharing the creative process with nature, simply giving the natural beauty of the wood a direction, a helping hand to be shown in its best light. I really think it’s like a collaboration.

Perhaps I don’t have the confidence to create something with utter control over everything, but I believe not seeking utter control over my medium is the defining characteristic of my work.

“Anything struggling to live is beautiful.”

What is true beauty for you?

I think when I make something, I unconsciously lean towards shapes made in nature, or of living things. Plants, trees, leaves, animals, the human figure.

As for why I do that, it’s because I think that living, or simple existence in this world is itself beautiful. There was a wood sculptor who said: “Anything struggling to live is beautiful.”

We’re all held down by the gravity of this planet, yet we all take in sustenance and struggle to grow up and out, and that leads to beautiful forms being taken. Similar with humans – as we are human, we have forever been using our own form as motifs for artwork , but by the same stroke, I gravitate towards mammals and other organic life, because they also have a will to live which I find beautiful.

On the flip side in terms of non-living things, a rock in the middle of a river, for example, having its corners smoothed by the current until it looks like an egg, eventually returning to nothing, can be beautiful. Perhaps the feeling of things returning to nothing is an ultimate expression of beauty.

Rediscovering Our Sensitivity for Materials

What sensations and awareness do you hope your works inspire in the people that bring them into their lives?

The main thing is that the person who invested in my work uses it in the way that they want to. But I also would like them to re-discover wood as a material.

Wood is such a convenient, useful and familiar material that has been used by humans for so long, and yet recently you don’t see many products utilizing natural wood. It might have a wood veneer or be printed to look like wood, but the use of real wooden products overall has been drastically decreasing.

So I want people to see real wood and feel that it was once a living thing, which is something humans should instinctively understand. Its texture, and the feeling it evokes in us, is completely different to resin or inorganic things.

It’s like when you were kids and used to play in the mud, or when you take your shoes off to wade in a river – you kind of remember something you were on the verge of forgetting because you are used to wearing shoes now. I want people to have that feeling when they use my products, and I want them to rediscover a sensitivity for materials.

Close to the Source

You have a base studio in Tokyo and a second one here amidst the forests of Mie prefecture. One in the largest urban area in the world and the other set amidst pristine nature.

What does each location awaken in you?

Being in Tokyo constantly feels stifling. As a woodworker it feels important to be close to the source of my materials.

In Tokyo, everything but the sky has been placed or made by people. It’s a huge contrast to Odaicho, where most of what you see is trees.

When you’re in the city you can order wood, and you can see the grain and the knots but you can’t appreciate how it got that way. When you’re in nature, you can view trees and see how they grew to be the way they are.

Man-made things are beautiful, of course. Architecture, product design, and all of those things. But the forms that things take in nature are ultimate. As humans, we are part of nature, so we can’t help but be influenced by it.

Witnessing how something grew in order to survive and thrive in a natural environment, evokes a different kind of respect for the unique shape and characteristics it has acquired in that very process.

So when I am here, I often work on pieces that maintain a lot of their original shape and imperfections. Like the large chairs shaped out of entire tree trunks, fashioned in the manner of a tree hollow large enough for children or adults to curl up in. These chairs are made to give people nostalgia about playing in nature. You can’t help but smile when you sit in them.

In Tokyo, I mainly work on smaller pieces like plates, bowls, spoons and interior items that often have a more polished and minimalist design or basic shape. Yet also there, I always strive to let the grain, color and pattern of the wood speak most elegantly through the shapes I select.

Reverence & Interbeing

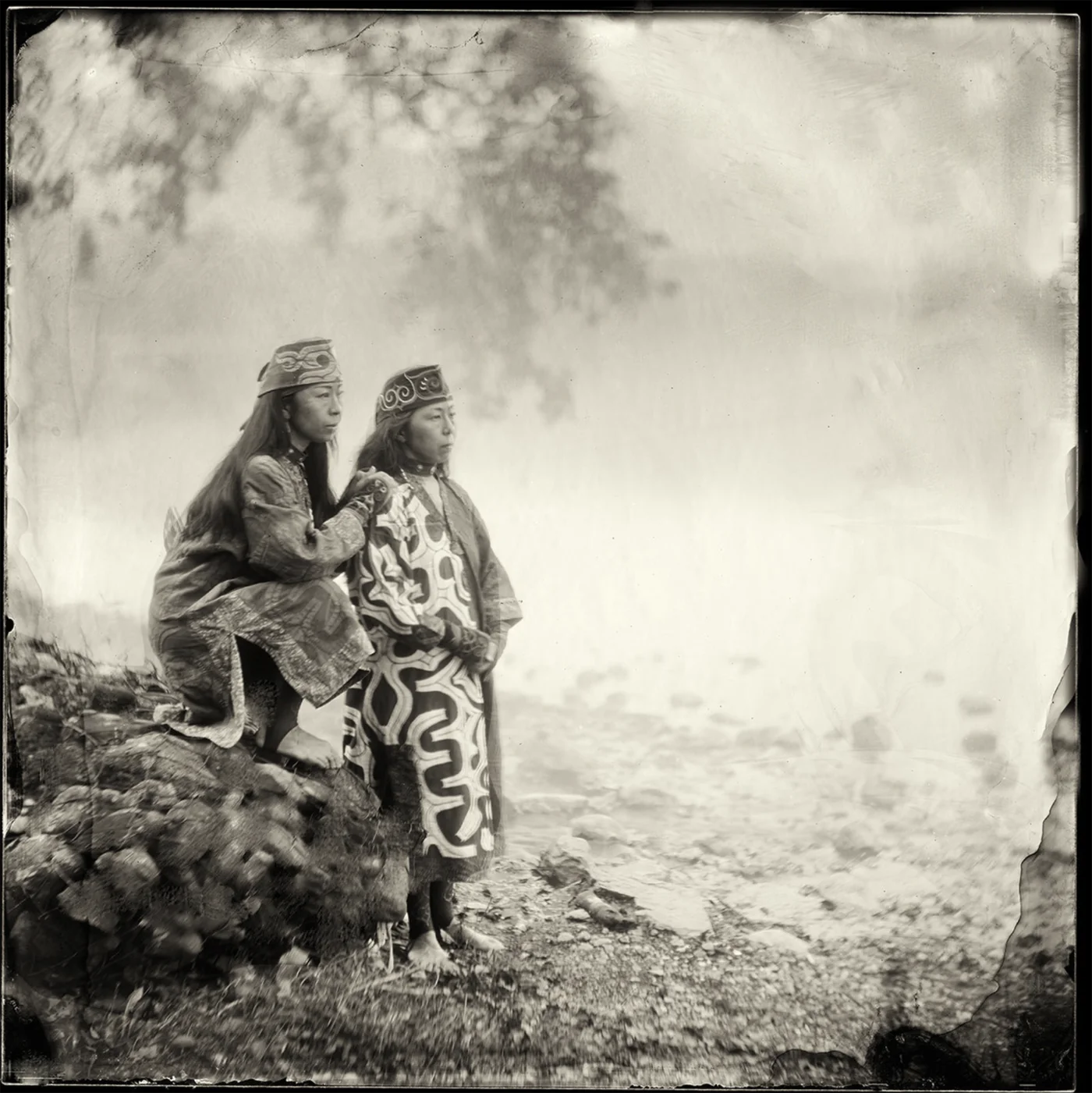

Your reverence for nature and wood feels close to Shinto. And you have previously shared how Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hahn’s concept of Interbeing resonates with how you see the world.

Could you elaborate how each informs your world in view and work?

I’ve always been deeply impressed with the architecture and design of shrines. I think that the people long ago who came up with these designs were supremely talented and had an eye for using materials to their utmost potential. It is truly genius design.

In terms of Buddhism, I very much respect Vietnamese Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hahn, who recently passed away. He taught that all things rely on each other to exist, terming it ‘interbeing’.

In one of his teachings, a student said ‘I want to know what I am’. In response to this, Hahn said ‘ask what a wave in the ocean is.’ A wave is a wave, and one of countless other waves, yet also inextricably part of one ocean.

In the same way, the trees we use for materials were once living things, which I strive to be conscious of the fact that we share this world with for a short period before passing on. I think this area overlaps with Buddhist teachings.

Knowing that you are everything yet nothing at the same time, in the immeasurably long life span of the world and understanding that trees too are part of this system.

Being Moved by Nature

What is your main feeling as you look towards the future?

Lately there’s been a lot of talk about SDGs at schools or companies, and all of them seem very well put together with all sorts of figures and action plans and so on. But what I find strange is that all of these discussions happen inside conference rooms, and not that many people in the discussion have actually spent time in nature.

Of course, it’s great that there are people who want to make a bad situation better, but I think being more in contact with nature will help propel these projects at a greater pace.

I think that a lot of people somewhat understand that nature is important, but I think not many people really get to feel it, simply coming and going to their place of work everyday. It would be great for schools and companies to conduct more activities out in nature.

I think it’s important for children and adults alike to know the joy of touching wood and making something from it. Being moved by nature is a great motivator to want to preserve and protect it. I would like more people to feel the unfathomable power and beauty of nature.