A Language Beyond Words

What is beauty for you?

For me, beauty is something that makes your heart race the moment you see it.

There’s no explanation or logic; it’s an immediate, visceral reaction. It speaks a language beyond words. You don’t analyze it with your brain; it simply strikes you.

I want to discover things that make my heart respond like that. I travel all over Japan in search of them.

I believe that even in difficult times, whether it’s war or the daily struggles of running a gallery, something as simple as seeing the clear moon in the night sky can calm the heart. Beauty has the power to help people. Anywhere. Anytime.

I often say: “Beauty is power.” It holds a profound meaning in life. It may not be quantifiable or easily defined, but it is essential.

In nature, too, take the male peacock, for example. His beauty plays a vital role in attracting a partner. And it isn’t only found in art or material things. Beauty is everywhere. In the middle of a city, even a single blade of grass pushing up through concrete can be beautiful.

So beauty, in all its forms, has meaning and purpose.

What gives meaning to what you do every day?

Gratitude.

Gratitude is my energy; what keeps me moving forward. Being thankful to the artists, being thankful to the materials they use, being thankful to everything that I attract into my life.

Each day these layers of gratitude continue to build upon each other.

The Beauty of Japanese Culture

How did you come to open the gallery?

From a young age, I was drawn to beauty, especially the kind shaped by human hands. That’s where it all began.

When I see something beautiful, I feel it deeply, and I want to share that feeling.

It’s like tasting something truly delicious and wanting to give half to someone else. And then that person shares it with another. This type of simple, generous sharing is what I hope to create through art, craft, and culture.

In 1995, the Hanshin earthquake struck the Kansai region. Before that, Japan had experienced an economic boom, but after the earthquake, the economy was devastated. That same year, there was also the sarin gas attack, and Japan found itself in a deeply difficult place, both socially and economically.

A year later, I found myself reflecting on what remained, and I realized: what Japan still has is culture.

I had never worked before. I was naive. If I had, I would have known how hard it is to run a business, to open and sustain a gallery. I probably wouldn’t have even imagined starting one during such a time of crisis.

But because I had no point of reference, I lived in a kind of “dreamworld.” I simply had hope — hope in art, and in the culture of Japan. That hope is what gave me the courage to open my first gallery, and it’s what still drives me today.

Feeling Connected

What is your aim today, as you continue to run the gallery?

First of all, I love Japan.

Seventy percent of the country is covered by forest, and Japanese people have always lived closely with nature; surrounded by it, shaped by it. Through the gallery, I want to create something that allows people to feel that connection, even in big cities like Tokyo or New York.

Art and craft aren’t separate from life; they belong in it.

What I hope to do is help raise the level of everyday living; to make life more cultural, more beautiful. Even if there are challenges in politics, business, or the economy, art and culture endure.

And in Japan, it is still possible to live a life full of both.

In the beginning, I didn’t know anything about how to run a gallery. I simply had a wish — to encourage Japan, to uplift it through art and culture, and to help restore a sense of pride in monozukuri (the spirit of craftsmanship).

But when I started visiting artists in their homes and saw the difficult economic situations many of them were facing, my mission changed. I realized that one way I could support them was by selling their work, by helping to sustain their lives through art.

How do you choose an artist you’re going to exhibit?

I don’t choose based on reputation or academic background. I look for something simple and sincere: whether their work is truly beautiful.

I go to solo exhibitions, galleries, even department stores; anywhere I hear about something interesting. I follow those leads myself.

And just as important is the relationship I build with the artist.

I always approach them with deep respect and gratitude. Gratitude for what they create and for the opportunity to work together. That spirit of gratitude forms the foundation of our relationship.

The first and most important thing is feeling grateful for being able to work with the artist. That’s everything.

Inori No Kokoro: A Heart of Gratitude

You present the work of a wide variety of artists, from all over Japan and across generations. What do they all have in common?

What they have in common is very simple: I love them all. [Laughs]

What I mean is, each one of them moved me deeply when I first saw their work, and that feeling made me want to share their art with others. That’s where everything begins.

So perhaps the real common thread is my passion and heartfelt desire to present these artists to the world.

But, there’s something very important that I believe we all share: what I call inori no kokoro, a heart of prayer and gratitude.

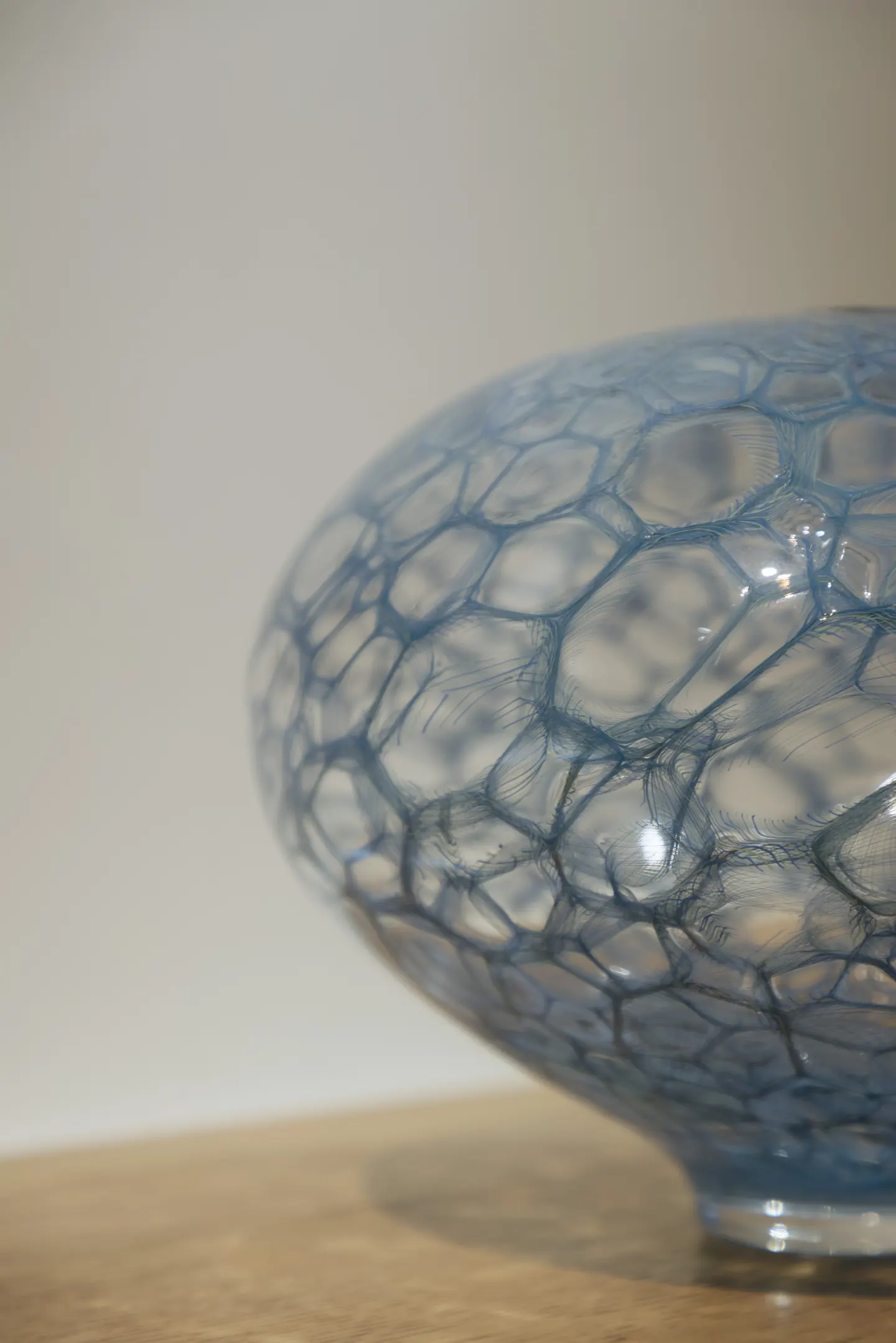

When they make paper, they’re thankful to the plants or trees they use. When they make ceramics, they honor the clay, its origins and its essence. This deep appreciation for the materials and the act of creating is something I resonate with very much.

Another shared value is the desire to support or uplift others, what we call sukui.

These artists don’t just make things; they create with the hope that their work might bring strength or comfort to someone else. Their mindset and outlook are full of care and reverence, and that spirit continues with the person who lives with the work.

To be honest, I don’t resonate with artists who don’t have that appreciation and who take for granted the ability to create. That kind of attitude wouldn’t align with the values of Ippodo.

What do you think it means to be a true artist?

For me, it’s less about whether someone is called an “artist” and more about how that person lives their life as a human being.

If, 100 or 200 years after they’ve passed away, their work still brings joy and meaning to people, then I believe they were a true artist.

I don’t connect with the kind of cynical stance where art is only used to critique or challenge society, or to make bold claims about changing the world.

I’m drawn to artists who create from a sincere place, who simply want to make something honest. That kind of art resonates more deeply with me.

Rooted in Tradition, Incorporating the New

Shu-ha-ri (守破離) describes the path of mastery in the Japanese arts: first learning and preserving the form (shu), then breaking from it (ha), and finally transcending it (ri).

How does this connect to the kind of artist you choose to work with at Ippodo?

The most important thing is that artists begin with Shu, the foundation. That means making many, many pieces at first. It’s through this repetition that they develop basic skills and solid technique. Without Shu, there can be no Ha or Ri.

Once an artist has truly grounded themselves in those fundamentals, they can begin to move into the next stage: Ha. This is where the artist starts to develop their own voice — they begin to find a purpose, a vision, a contemporary sensibility. They start to question the tradition while still working within it.

For me, it’s not enough for someone to simply continue producing traditional work in the same way. That alone doesn’t interest me.

But when an artist who has mastered the foundation starts to evolve, to combine those traditional skills with modern ideas, materials, or technologies, then they move into Ha, and maybe even Ri. That’s where real creativity and innovation live.

I’m drawn to work that is rooted in tradition but that also incorporates something new. That’s exciting to me. It’s moving forward, not just looking back.

But even then, the foundation remains essential. The basics must always be there. Shu is the base of everything.

Restoring a Sense of Pride

What have you learned by collaborating with so many artists over the decades?

I’ve learned from how each artist lives their life.

Every single one of them is different, what they value, what they hope for, and how they build their life. By witnessing the way they live, I’ve learned so much myself.

For example, Take Kishino Kan, is a ceramicist. He chooses to live very strictly, like a monk. His lifestyle is incredibly disciplined. But the works he creates are elegant and pure; very refined.

Another example is Terumasa Ikeda, a lacquer artist. He studies ancient buildings in Cambodia, and East Asian architecture from hundreds of years ago. He challenges himself to reach that level of mastery.

These two artists are very different in their approach and polar opposites in a sense. The first turns inward, deepening himself from within. The other looks outward, learning from existing structures and from history.

But what they share is an intense passion for creating.

Being alongside artists like them, seeing that drive and sincerity, it warms my heart and encourages me to keep going.

What are you trying to convey to your clients — Japanese or non-Japanese — about Japanese art and craftsmanship?

For Japanese clients, there is still a strong fondness for Western culture.

Many people admire Meissen porcelain or collect Lladro dolls, that Spanish brand is very popular here. But I want to remind them: look at what Japan has. Look at what Japan is making.

My role is not only to present these works but also to continue learning so I can share the deeper story behind them. To help people reconnect with the richness of their own country.

In doing so, I also hope to restore a sense of pride.

Experiencing a Way of Life

There was a time, around 40 years ago, when people used to say “Japan is number one.”

Since then, in areas like the economy, chemistry, and technology, Japan’s position has declined. But even if many things have changed, what remains is our art and culture.

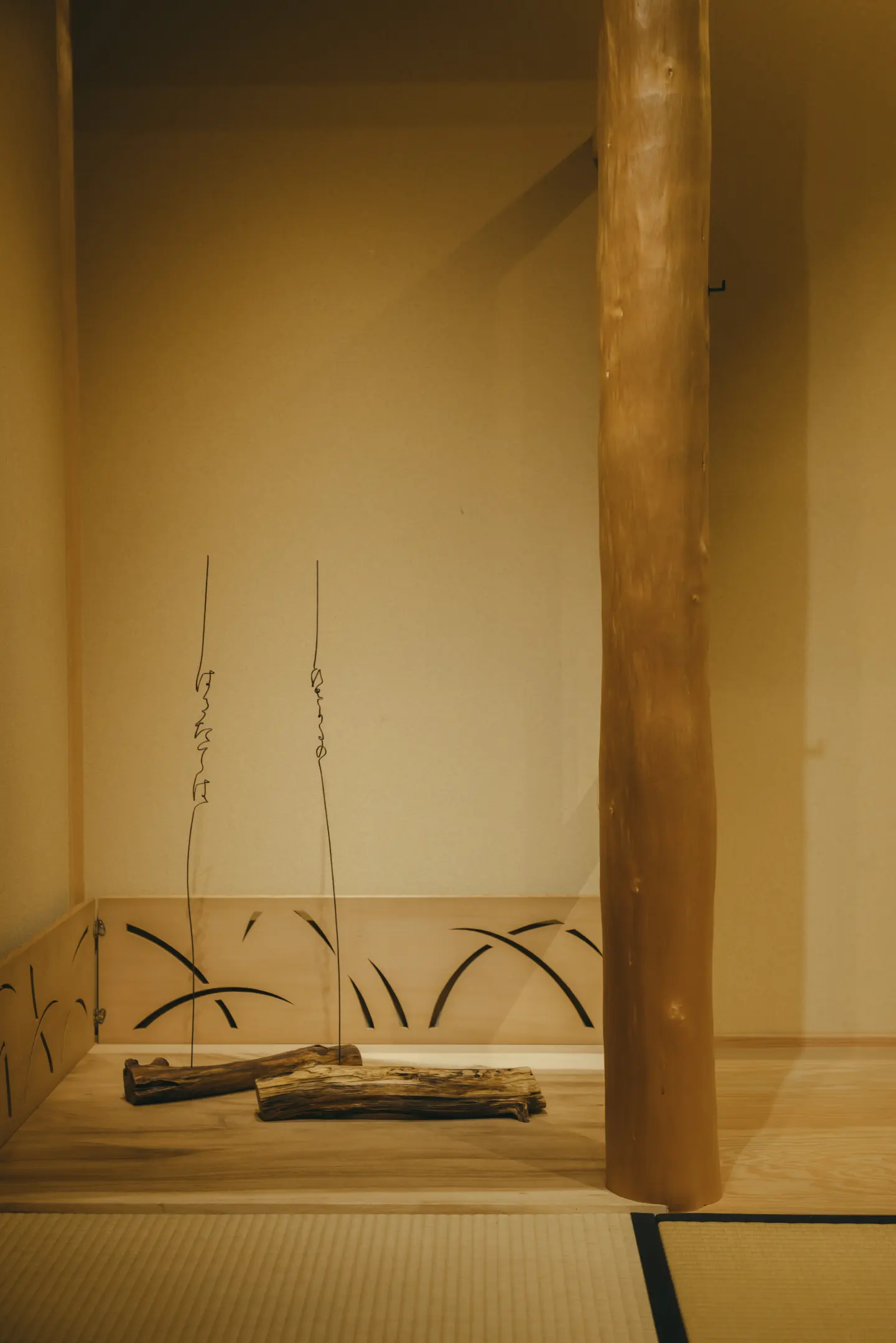

And when I speak of Japanese art and culture, I mean something that is embedded in everyday life. That’s why I created this room inside the gallery: to show people how to live with Japanese sensibility, how to live with beauty.

It’s not just about viewing art, but about experiencing a way of life.

For non-Japanese visitors, it’s different. Those who come to the gallery already love Japan. With them, it’s more about deepening that appreciation.

Could you say more?

I want visitors to the gallery to see beyond the artwork and come to understand the world behind it. Why was this piece made? What was the artist experiencing? Were they joyful? Were they struggling? That emotional and environmental context is part of the work’s essence. It shapes what stands before you.

And I want them to understand that collecting art is not only a personal experience, it’s an act of support. It helps sustain the artist’s livelihood, and contributes to the legacy and continuation of Japanese traditional culture.

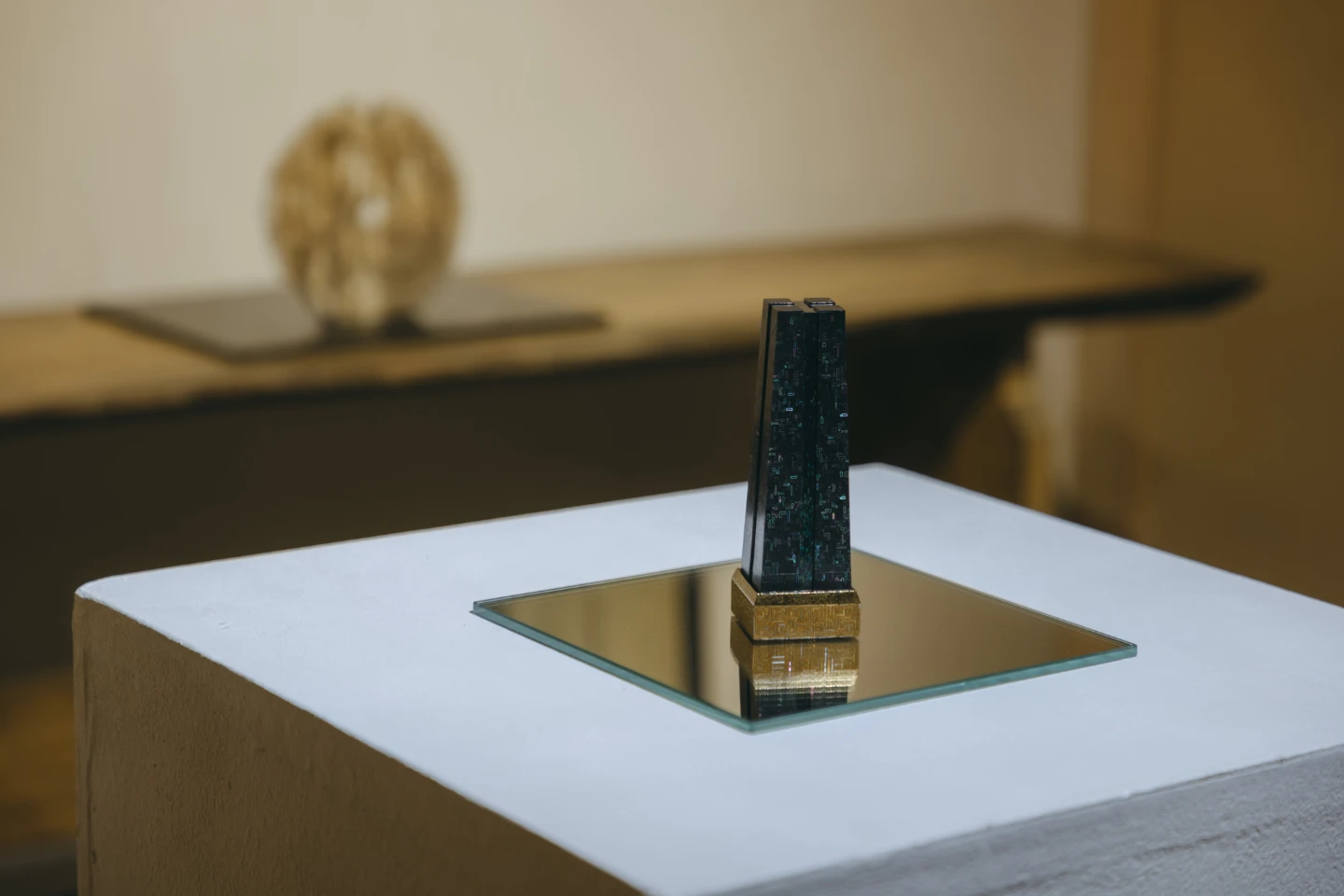

As a gallerist, I see it as my responsibility to set the stage, to create a space where each work can truly shine, and to offer that extra something that allows the piece to come fully alive.

It’s like performing an opera; if it takes place in an opera house, it’s a completely different experience than staging it elsewhere. In the same way, how an artwork is presented can dramatically shape how it is felt and understood.

And this often deepens with time.

New works have not yet been wrapped with time, but they will. That’s something very important to remember.

I once visited a client’s home, and they had purchased a painting from us ten years ago. After all that time, the work looked more beautiful than it did when it was first bought.

Becoming Someone Who Offers Beauty to Others

Why do you think that is?

The collector said, “I really like this painting. I’m happy to see it every day.” That kind of feeling, of living with something you love, makes the artwork shine.

The same goes for matcha bowls. If a bowl is easy to hold, easy to drink from, and brings joy through use, that care and attention adds to its beauty over time. The artist may have shaped 70 percent of the work, but the remaining 30 percent is completed through the hands and heart of the person who uses it.

That’s why I always encourage people to cherish the works they bring home. If I can tell the story of a piece and present it with care, the value of the artwork deepens naturally.

Is there a final message you would like to share with our readers?

Everyone is a part of nature.

Whether it is the artist making the artwork, the person looking at it, or using it, everything is part of nature.

Whenever you face difficulty in life, keep something beautiful nearby. Remember, “Beauty is power.” Try to be someone who offers beauty to others. That is the message I hope to pass on.

I hope you can become someone who finds beauty in those small, overlooked moments. Even when you’re tired or worn down, notice the grass, the moon, the wind, or the color of something green that catches your eye. Be that kind of person.

Through these kinds of acts the world will become more peaceful.

It might be simple, but that’s what I feel in my heart.