True Well-Being

The term “Well-down” is a concept you created to offer a counterbalance or alternative to a culture that seems hyper focused on well-being. Focusing instead on accepting ourselves in our full humanity, with light and dark sides.

Could you share what ‘well-down’ is and why you introduced it?

We came up with Well-down around 2019 or 2020, right in the middle of the global COVID pandemic.

At the time, a lot of people were talking loudly about well-being. Often, those same people weren’t drinking or smoking, or doing anything considered “bad” for the body. It felt like the concept of well-being was becoming too polished, too narrow, too idealized.

But originally, well-being wasn’t just about doing all the “right” things. It was about balance—between work and life, between outer stability and inner peace.

To me that sounded a lot like something you find in Japanese Zen: the idea of knowing sufficiency, or what in Japanese we call ‘taru wo shiru’ (足るを知る)—being content, even when things are simple or lacking. Understanding that you don’t need everything, and choosing to be okay with that.

“Well-down” is a state in which even if you deviate from society, there is no mental burden and you are naturally satisfied with yourself. Relaxing into yourself just as you are, without any pretense.

But what we were seeing felt different. It was more like: only do what’s good for you, cut out everything else. And the truth is, people don’t work like that. People overdrink sometimes. People want to smoke now and then. Even the most admirable people have moments where they want to cut loose.

So we started thinking: let’s acknowledge that side of being human too—the cravings, the messy parts. Let’s make space for it. That became our declaration: Well-down.

The word well-being had started to feel too polished—like it only allowed for the bright, healthy parts of ourselves. As a response, we coined Well-down to say: it’s also okay to be tired, to carry weight, to be human.

For us, that’s what real balance looks like.

Welcoming our full humanity. The light as well as the dark.

Cleansing My Own Heart

When and why did you first begin studying tea?

I started learning tea ceremony when I was 15. After I graduated from junior high, I went on to high school, but I dropped out after my first year.

After that, I ended up becoming an apprentice at a bookstore in Tokyo. The owner of that bookstore had been raised by a tea master. Through that connection, I was introduced to the Omotesenke school of tea ceremony and began learning under a teacher.

What has the journey of studying tea under your master been like for you?

I remember sitting alone in a tea room, where the only sound was the water quietly boiling in the iron kettle. As the steam rose, I could see the moss-covered garden beyond it.

Something about that scene gave me this deep sense of nostalgia, like I’d been there before. At the same time, it felt incredibly refreshing, like a weight had lifted. All the dust and clutter that builds up in daily life just melted away in that moment.

It made me think: There’s something good here. Something worth pursuing. And maybe, by coming back to this over and over, I could slowly begin to cleanse my own heart too.

Around that time, I also came across Zen.

The bookstore where I was apprenticing carried a lot of Zen books, so I started reading them. That’s also when I began practicing zazen (seated meditation) on my own. I had already heard that tea ceremony and Zen were deeply connected.

At first, learning tea was all about memorizing forms—just trying to get everything right. But after a while, once those forms start to live in your body, your movements become automatic. You’re moving, but it feels like you’re completely still. That feeling—it’s really similar to what happens in zazen, that stillness that settles over you.

So I started to feel like maybe through this repetition—even something as simple as drawing water—there’s this paradoxical wisdom, like not drawing, yet drawing. My teacher used to say, “Water is drawn without drawing.” I think that kind of teaching—that kind of mystery—exists in both Zen and tea. It feels like one of the deeper aspects of walking the path—of mastering a dō.

Softening Our Grip on Things

Could you share how Zen has shaped your view on life?

I first tried zazen when I was fifteen. At the time, I was just vaguely curious—I’d sit and try it out. I kept it up for a few years, though not consistently. Around 18 or 19, I forgot about it for a while.

Then, just before I turned 30, I came back to it. I was running a company, things were hectic, and I was totally worn out. I realized I was juggling too much, so I thought I’d try sitting again.

And it made me realize—zazen is really about letting go. Letting go of thoughts, attachments… all the things we end up clinging to without even noticing.

That simple act of releasing—that’s where the value lies for me. It’s like a quiet, personal ritual of softening your grip on things.

What would you say the essential value of Zen in today’s world is?

For me, Zen is just everyday life. Cleaning, cooking, brewing tea—ordinary things we do every day.

The way I see it, Zen doesn’t separate you from the world. Everything is part of the same whole. There’s no dividing line between you and what you’re doing. So whether you’re eating, sweeping, or sitting in a tearoom—Zen is always there.

It’s not about whether something is “Zen” or not. It’s about how you do it. Are you fully focused on the act of eating while you eat? Are you really present when you clean? That kind of attention—that commitment—is what matters.

You could call it mindfulness, maybe. But for me, that’s what Zen really is. A way of being that can exist in any part of life, wherever you are.

So over time, Zen has become something like a life practice. A guiding thread running through everything. Like something stuck to my back—always with me.

And when I start to forget it, I notice my posture slouching (laughs). But when I remember—when Zen is there—it’s like my back straightens again. It keeps me centered.

Meditation in Motion

How do tea and zazen connect or intertwine for you?

For me, zazen is a still meditation. But sadō is meditation in motion.

When I’m in the middle of zazen, all sorts of things fall away. It gives me this light, unburdened feeling. And the Way of Tea is about moving while staying in that same state. That’s why I think of the tea ceremony—especially the formal practice of sadō—as a kind of entry point for weaving Zen into everyday life.

Zen monks say that when you sit regularly, daily life begins to shift. You might drop into a flow state while sitting, and gradually, that same clarity starts to appear in ordinary moments. You come home, start cooking or cleaning, and think… this feels just like when I was sitting zazen. That sense of stillness stays with you.

When I practice tea, it’s the same feeling.

The movements—refined over hundreds of years—have been shaped to eliminate anything unnecessary. Every action has a purpose. This is placed here, that is picked up like this—each step pared down to something clean and intentional.

Knowing What is Enough

How does that connect to the Zen term ‘chisoku anbun’?

I think a lot of people believe that the more income you earn, the better. But once that kind of desire starts to inflate, it doesn’t really stop.

For example, you might say, “I’m fine with 150,000 or 200,000 yen a month,” and build a modest life around that. And if you can live simply and still feel fulfilled—that’s a really healthy mindset.

But when that no longer feels like enough, and you start thinking, “I need more—300,000, 400,000, 500,000…” your spending grows too. And it still doesn’t feel like enough. Then you’re scrolling social media, seeing friends go on trips, and suddenly you want that too. The cycle keeps going.

What I try to do is press pause on all that. I try to appreciate what I already have, and build a humble, grounded life around it.

That, to me, is chisoku anbun (知足安分)—knowing sufficiency, being content with what is.

And in a way, it’s the same as what we were talking about earlier. Even with something like health: wanting to eat better, do yoga, quit smoking—those seem “good” on the surface, but taken too far, even that can become another kind of attachment.

So I think—what if it’s okay to be unhealthy sometimes? Maybe not obsessing over health is actually a healthier state of mind. Not being greedy includes not being overly attached to being “healthy.”

So to me, chisoku anbun is deeply connected to our Well Down philosophy— our version of well-being. They’re both about embracing what’s here, now. And not chasing what’s always just out of reach.

“Stay Poor.”

Your tea master’s mother once told you ‘You are a tea master, so stay poor.”

How do you understand and see those words now?

In tea, we use a cloth called a fukusa—a square piece of silk, often purple, like a handkerchief. My teacher lives in Tokyo, and I go back and forth between his tea room and mine in Kyoto. One time, I left my fukusa behind in Kyoto.

So I bought another. A cheap one costs about 5,000 yen. I said, “I keep forgetting it, so I figured I’d just get a second one.”

But I was told—No. Just because you have money doesn’t mean you should buy your way out of carelessness.

At first, I was surprised. But what my teacher’s mother was saying was: don’t lean on convenience. When you live within modest means, that’s when creativity and intention really begin to grow.

If you keep throwing money at small problems, it adds up fast—and you lose the chance to learn from them. Being poor, or living with less, is hard. But it has its own quiet value. It makes you ask: with what I have right now, how can I be fulfilled?

That kind of creative problem-solving becomes its own form of wealth. When she told me, “A tea practitioner should be poor,” it stayed with me.

Especially now, when society’s default is to earn more, buy more, consume more. These things feel less like choices and more like compulsions.

So when she said, “Stay poor,” it felt refreshing.

If you can truly master living modestly, you get good at life. You invent richness from simplicity. And to me, that’s very close to what Zen teaches.

The True Training Hall

You once saw a scroll with the expression ‘Jikishin kore dojo’. What does that expression mean and what about it resonates so deeply for you?

Jikishin kore dōjō (直心是道場) — “A sincere heart is the true training hall.”

There was a time I seriously considered leaving everything behind to become a Buddhist priest. But I was still running a company then, and I couldn’t just walk away from it all. After a few months, the urge to join the monastery began to fade, and I started thinking—maybe I should just do my best right where I am.

Not long after, at one of our monthly tea gatherings, my teacher hung a scroll in the tearoom with the words: Jikishin kore dōjō.

Jikishin means a forthright, unclouded heart. If you have that, then wherever you are can be your place of training.

That hit me deeply. I had been thinking I couldn’t grow unless I changed my life completely—went to a temple, became a monk. But that moment helped me realize: growth doesn’t require escape. It asks for sincerity, right where you are.

I think it was my teacher’s way of gently trying to tell me that.

Of course, it’s natural to long for more— a place, a role, a life change. That longing can be meaningful, even necessary. But when you don’t end up going, or when you can’t go, that doesn’t mean you should give up or stop halfway.

Maybe you didn’t make it to where you wanted to go. But you’re here. So where you are—that’s your dojo.

That mindset, that commitment, it connects back to what we talked about earlier. Chisoku anbun, contentment with what you have.

Whether it’s your personality, your environment, your station in life—don’t run away from those things. Face it with gratitude and resolve. This is the place where you practice, and grow.

For those of us living in the world day to day, Jikishin kore dōjō is a powerful reminder. A connective tissue running through our lives.

It’s one of my favorite teachings.

Connecting Tea & Shisha

How did you enter the world of shisha and what led you to open a Shisha cafe in Tokyo?

I first tried shisha when I was around 20. At the time, I was working in video production. There was this shisha café in Shimokitazawa, actually the very first one in Japan. A friend took me there.

And I was struck by something. It gave me the same kind of inspiration I’d felt in a tea room. Everyone was sitting around a square bench in this stone-walled space, with the shisha in the center. People were gathered around it, chatting, relaxing—and it really reminded me of a tea room.

Just like in tea: people sitting around a source of fire, enjoying quiet conversation. That similarity really hit me. I remember thinking how interesting that was.

How did you begin to connect the worlds of shisha and tea and develop and introduce a tea smoking ceremony?

Of course, shisha and tea weren’t originally connected in any way. I started smoking shisha at 20, opened my first shop at 23, and now I’m 36—so it’s been 13 years.

Over time, I began to notice how many similarities there are. Both use leaves—plants prepared with care. In both cases, you use water, and either inhale or drink what’s produced. The effect on the body and mind is also immediate and noticeable.

With tea, you get alert, sharp—it wakes you up. With shisha, some people say it clears their head, others say it relaxes or dulls them a bit. Either way, there’s a direct impact. And both involve fire, water, and often—though not always—sharing the experience with someone. When you look at it that way, the two are almost the same thing, just in different forms.

The difference is in the cultural background. Japanese tea ceremony came from Chinese tea-drinking customs, which were passed down and eventually formalized into a way of life in Japan—a path, a dō.

Shisha doesn’t really have that kind of structure or philosophy. It’s been around for 400 or 500 years, and while there are different styles and customs, it hasn’t developed into a practice or a path—a way to live or reflect, or engage with spiritually.

So my idea is: even though tea and shisha are so alike, they’ve grown up differently. But maybe by using the mindset and structure of tea—its way of doing things—we can nurture shisha in the same way.

Tea has already become a dō (a “way” or “path”), but shisha hasn’t. I want to borrow from the world of tea to help shape shisha into a path of its own—to make it a dō, too.

Ochill Kyoto

Together with Wataru Kiruta you founded Ochill Kyoto.

What makes this space so special for you and what is the vision behind it?

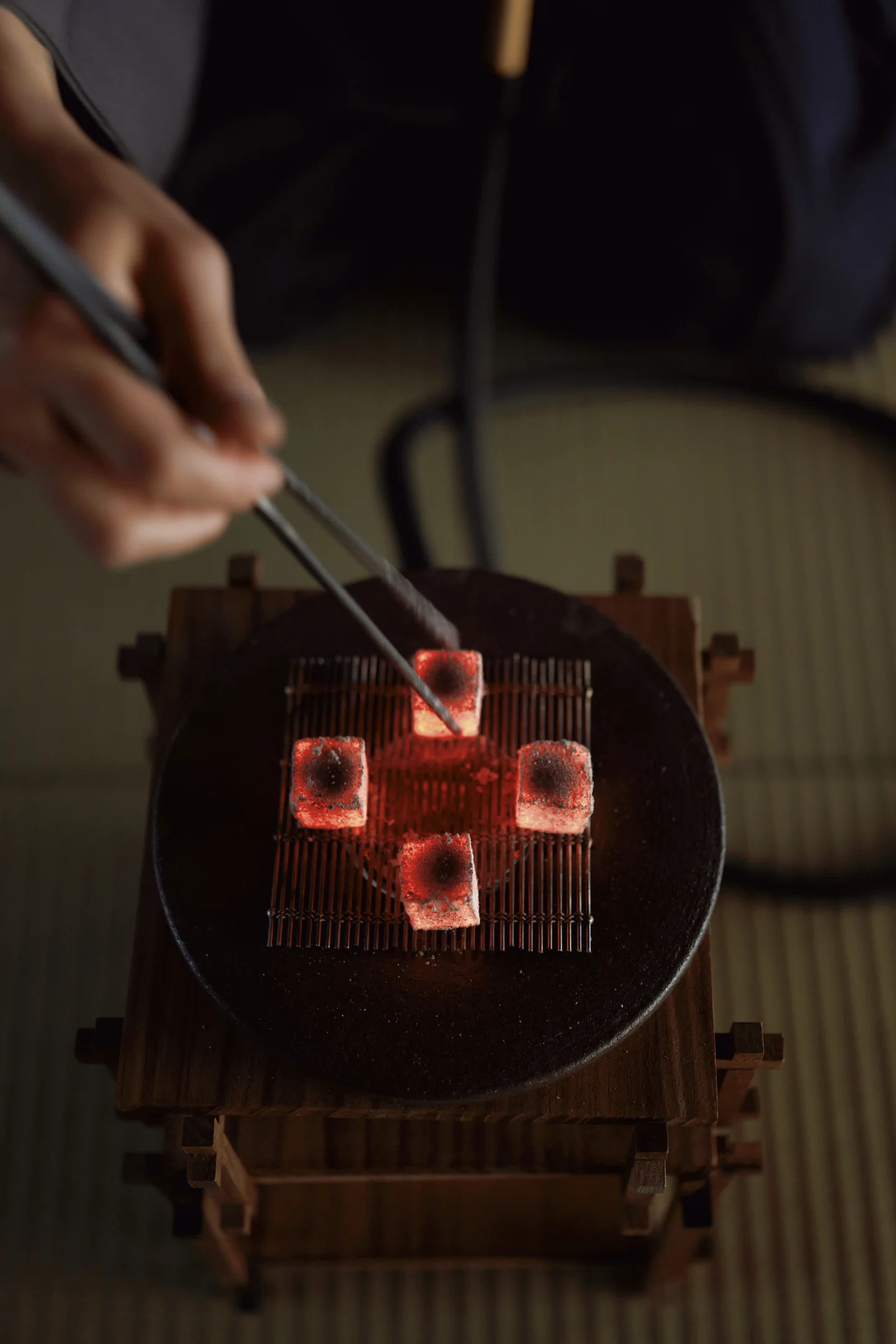

What we’re creating here is a space for sipping tea through breath—a tea you inhale.

We opened Ochill Kyoto in 2022, but even before that—around 2018—we had already started researching suu ocha, or “ChaKō (Tea Leaf Hookah),” sometimes called tea incense.

Eventually, we wanted a place where we could serve this tea and also embody the philosophy we’d built around it. A place that welcomes everyone just as they are, and invites them to relax into that.

The tea we use most often comes from Uji, in Kyoto, so we naturally wanted to root the space here. We renovated one of the old machiya townhouses and transformed it into a modern tea room—not just to serve tea, but to deepen the experience.

For us, ChaKō is a kind of moving meditation, too. We want guests to leave feeling as though they’ve meditated for 30 minutes, an hour, maybe even longer.

Let’s say you spend an hour sitting zazen, or an hour inhaling tea—someone might ask, what’s the difference? But people are different. Some can sit zazen easily. Others can’t sit still—they’re not in the headspace for it. On the other hand, some might be able to inhale tea but not feel much from it. That’s okay too.

What we offer is a space to inhale and exhale, surrounded by tea aroma and smoke. It might seem like a small thing, but for some people, that simple, sensory experience becomes deeply meditative.

Many guests leave feeling refreshed—like they’ve unknowingly let go of something heavy inside them.

I believe creating a space where we can meet and accept ourselves and others as we really are is important. That to me is true well-being.

What is beauty for you?

For me, beauty is the absence of corruption. Or maybe you could say, the absence of decay, when something isn’t spiritually dried out.

Because to me, ugliness—or something being “dirty”— is when the spirit, the ki, has withered. So, when things are full of energy flowing freely, not stagnant—whether it’s a place, a person, a mindset, I call that beautiful.

It’s a space or presence where everything is in motion— circulating, alive.

That is where beauty truly lives.